Air Mail

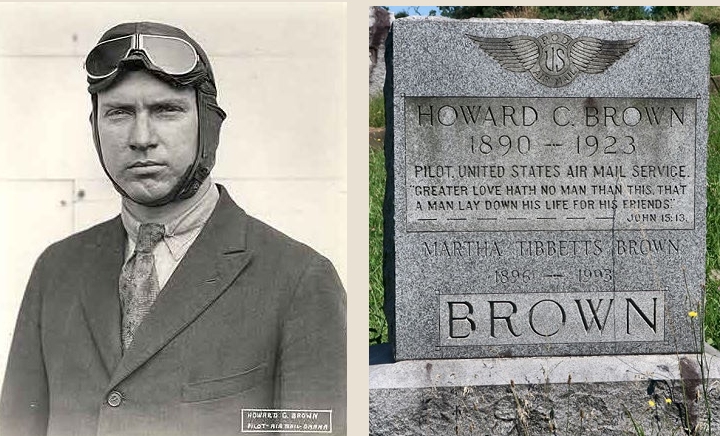

Howard C. Brown buried in the Spring Hill Cemetery, Charleston, WV.

I

stumbled unto the headstone you see above and decided to look this

fellow up. While we learned a lot about him, we don't know why

Howard C. Brown was laid to rest in Charleston's Spring Hill Cemetery.

|

|

Howard C. Brown was born in Moxahala, Ohio on September 15, 1890. He

married Martha M. Tibbetts on June 15, 1921. Brown had graduated from

West Virginia University and was an electrical engineer with Western

Pennsylvania Power Company from 1914 to 1917. Later that year, he worked

as an engineering designer at Diesher & Sons, followed by a stint

in the same position at Stone and Webster from 1919 to 1920.

Brown attended Princeton ground school in 1918. He was a flying cadet

at Love Field, and then took bombing training in 1918. Brown served in

the army from 1917 to 1919.

On August 1, 1922, Brown, representing the Air Mail Pilots of America,

wrote to Second Assistant Postmaster General Paul Henderson, who was in

charge of the airmail service, regarding an "Omaha Bee" article which

quoted Henderson as saying the airmail pilots were a "temperamental lot

accustomed to too much freedom in the army, and in my opinion over

paid." Brown said that he and the other pilots were understandably livid

at the quotation and wanted to know what Henderson was up to. In his

defense, Henderson denied ever saying anything like that, and charged

that the paper's reporter had made up the quotation for circulation.

While making an emergency landing on February 26, 1923, Brown tore down

two fences, in all about 250 feet of wire and posts. His aircraft then

ran into a soft and muddy wheat field where it became stuck. Mr. Klenke,

the owner of the property, helped Brown dig out his plane, get it back

into shape and even helped him take off again. The postal service

received a bill from Klenke for $30.90 for the damage Brown's landing

made to the farm.

On December 6, 1923, Brown was flying de Havilland airmail airplane

#318 from Cleveland to Chicago in relatively clear weather. At 10:30

a.m., W. H. Sedgwick, a postal employee at Castalia, Ohio, watched as

Brown's airplane tumbled to the ground and crashed and burned. Badly

injured and burned, Brown survived the crash and was taken to a

Sandusky, Ohio hospital. He was able to talk about the crash before

dying of his injuries.

Following the crash, investigators learned that Brown had spoken to the

local postmaster when asked if they should notify anyone. Brown

responded, "Tell my wife the control broke and I got a bump. I am

injured but not badly. Have a broken leg and will not be out for few

days. She may come here but its not necessary for I am all right."

Later, to a pair of airmail mechanics, he said, "I am not so bad; I

guess I have a broken leg and my nose is gone. Something went wrong with

the control assembly. I thought I could make Bryan. The universal

control broke and I lost control of my ailerons and elevator. I had a

ceiling of between 200 – 300 feet." Howard Brown died at about 5:30 p.m.

that evening following an internal hemorrhage.

|

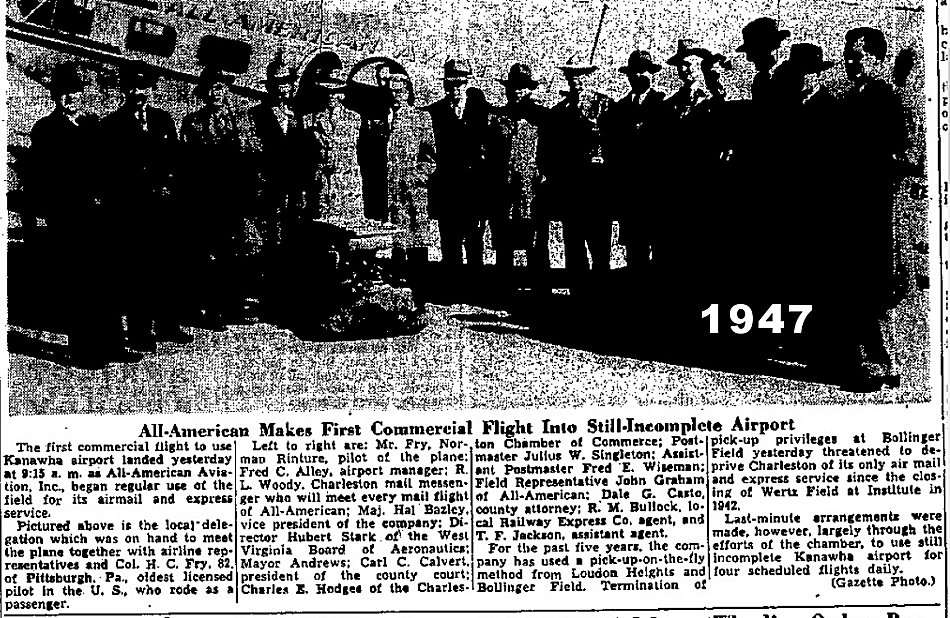

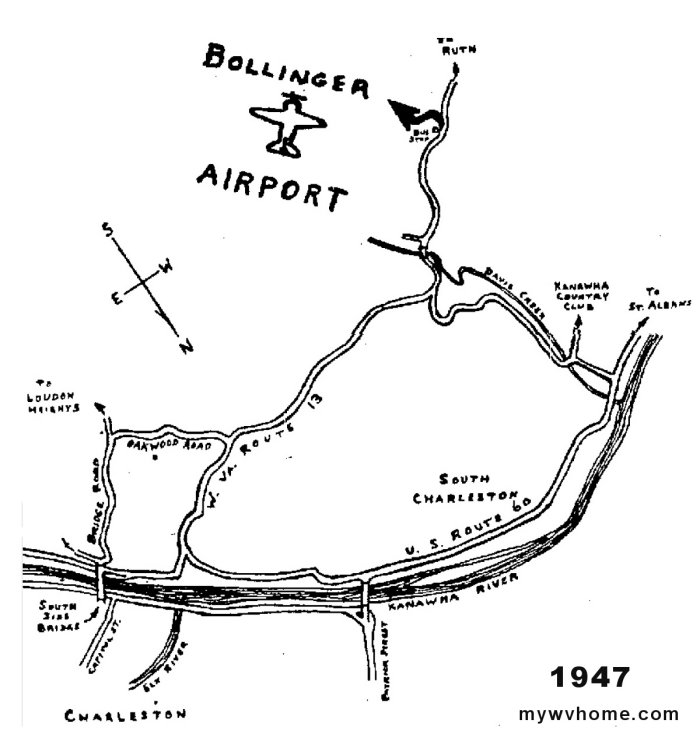

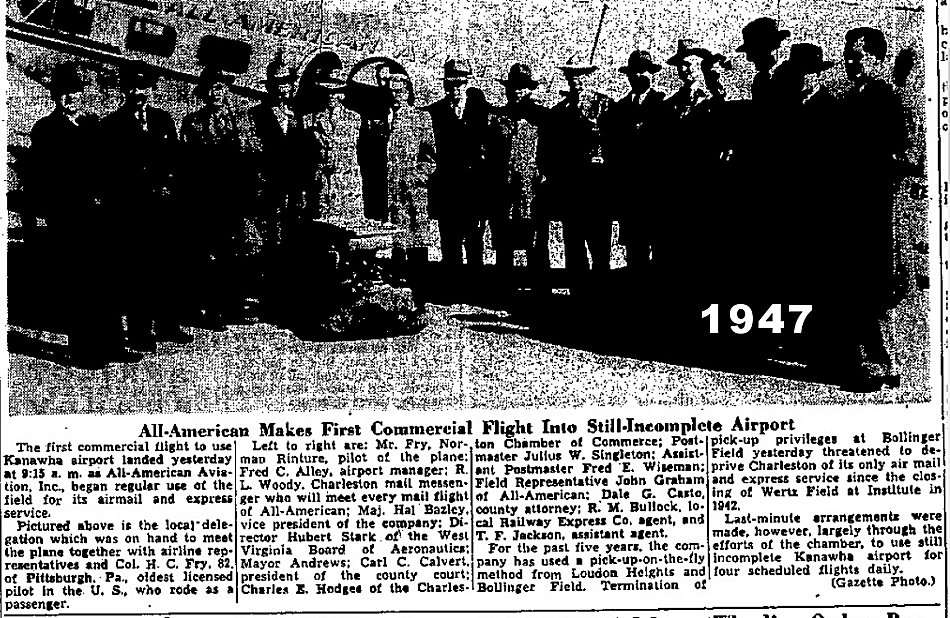

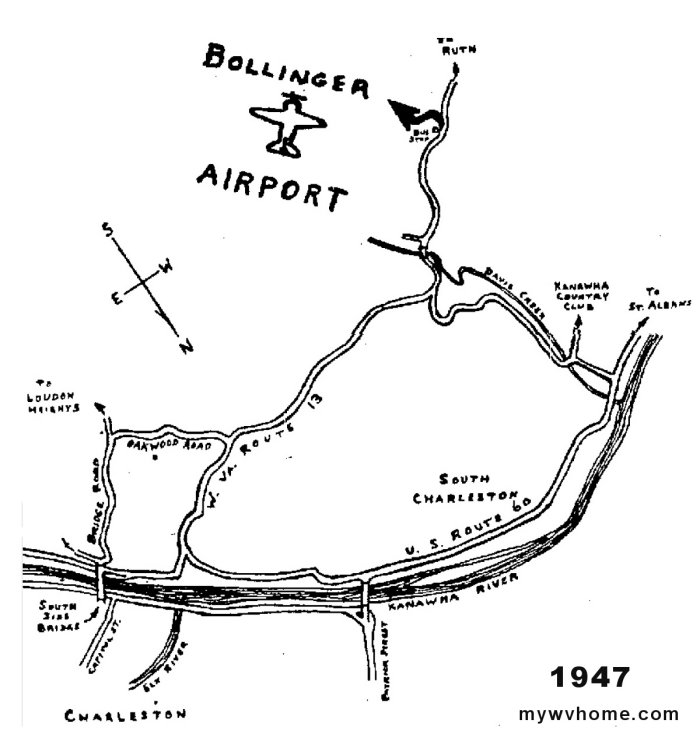

"On the fly" airmail pickup over Bollinger Field just outside of Charleston WV

"On the fly" airmail pickup over Bollinger Field just outside of Charleston WV

On April 12, 1939, a bright red Stinson Reliant plane swooped down out

of the sky in Latrobe, Pennsylvania snatching a container of mail

suspended on a rope between two poles. This event kicked off a unique

chapter in airmail history. At that time, airmail service was restricted

almost exclusively to metropolitan centers, out of reach of the

majority of the country's population.

But Dr. Lytle Adams, a dentist and part-time inventor, believed that

airmail service could be expanded to rural areas. Adams had became

intrigued with the potential of the burgeoning field of aviation. Adams,

with the assistance of Boeing engineers, developed a pick-up apparatus

in 1928. Dr. Adams quit his dentistry practice to travel the country

promoting this innovative new system. Because he envisioned bringing the

pick-up system to all of North and South America, he named one of his

speculative companies All American Aviation (AAA), and the system was to

be known as Air Pick Up.

By 1938, Adams had depleted his own fortune promoting his scheme.

Fortunately, he met Richard du Pont, a wealthy young aviation

enthusiast, who purchased a controlling interest in AAA. Excited about

future prospects, the men began purchasing planes and hiring pilots and

staff to make the company operational.

Although the Post Office Department was indifferent to Adams & du

Pont's plans, Congress, led by Jennings Randolph of West Virginia, was

supportive of the plan. Randolph's constituents were among the first to

be served by Air Pick Up. As a result of his support the service was

authorized by Congress as an experiment. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

signed the bill into law on April 30, 1938 and the first scheduled Air

Pick Up service began on May 12, 1939 flying two experimental routes.

The first route went from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia. The other went

from Pittsburgh to Huntington, West Virginia.

The planes chosen for the service were rugged Stinson Reliants, a

tight-turning airplane superbly adapted to flying around hills and

through valleys. For the next ten years a fleet of these planes provided

Air Pick Up to locations in the northeast United States that could not

be served by regular airmail service. Adams and du Pont modeled the

pick-up technique on the Railway Mail Service's Mail-on-the-Fly service.

The Stinson, painted bright red for easy identification, had a long

take up boom with a hook and a winch that operated through an opening in

the fuselage. Traveling between towns at 110 miles per hour, the

Stinsons collected and delivered mail and express packages at each

community without landing.

A pick-up flight started in the morning at the main airport where mail

and express accumulated from all over the country were loaded for route

stations. These stations received their airmail and express by Air Pick

Up the same day it reached the terminal city. At each route point, a

messenger collected cargo at the local express agency, mail from the

Post Office and drove to the station site where he rigged a portable

station for the pick-up. The station consisted of two poles some

fourteen feet high and twenty feet apart a container of mail was

attached to a rope stretched between the poles. An experienced messenger

could set up the station in about two minutes. The messenger monitored

flight status on a company radio.

The Stinson flew in and swooped down over the station, first dropping

the incoming mail in a cargo container, then flying twenty feet off the

ground and lowering its boom between the poles so that the hook engaged

the rope. This was connected with the winch, which paid out rope to

absorb the shock and then reeled it into the plane. In a few seconds,

the plane was out of sight headed for another pick-up. Inside the plane

the flight mechanic opened the container and took out several labeled

mailbags which he transferred to the appropriate bins.

Since many of these communities did not have airports, the pick-up

station was set up on golf courses, pastures or even cemeteries on the

edge of town. Most stations were located in the Allegheny mountains,

which had gained a reputation as the graveyard of aviation during the

early days of airmail service thanks to inhospitable terrain and

weather.

In the first year of service, All American Aviation flew over 438,000

miles, making over 23,000 pickups and handling 75,000 pounds of mail and

6,500 pounds of freight without a single casualty. With the reliability

of the system proved, AAA received a certificate of convenience and

necessity to engage in air transportation with respect to property and

mail. It was called Air Mail 49.

As the second year of operation began, the AAA Stinsons flew four

flights daily on five different routes radiating from Pittsburgh to

towns and villages in six states—Pennsylvania, New York, West Virginia,

Ohio, Kentucky and Delaware.

After America entered World War II in 1941, military enlistment and

letter writing soared. All American's pick-up service grew as the volume

of airmail flowing to men in distant theaters of war increased. The

fleet of Stinsons was expanded to eleven planes, and the workforce grew

to hundreds of employees. However, even during World War II, when it

carried its largest volume of airmail, AAA's air transport division did

not break even. In fact, any profit the company made was the result of

military contracts placed with the engineering division. The company

argued unsuccessfully for a higher reimbursement rate from the Post

Office Department.

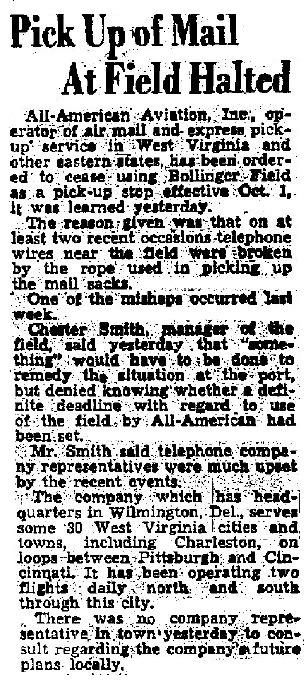

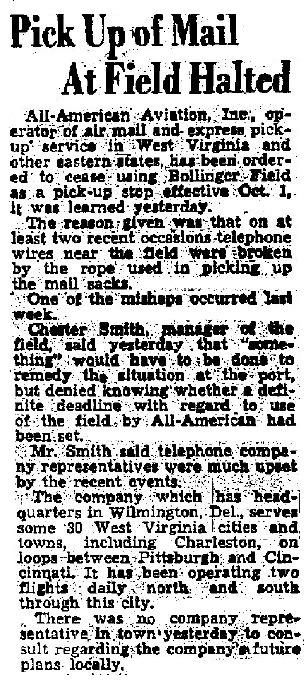

After the war, the volume of airmail carried by pick-up decreased

dramatically. To make up for those lost funds, AAA requested for

additional route miles, but were denied. For one thing, postal officials

argued that if pick-up was losing money on its present routes, why

expand it? Another explanation was the growing success of the Highway

Post Office Service, which began in 1941. Highway Post Office Service,

using clerks on moving buses to sort and carry mail between small towns,

proved to be a more efficient way of improving mail service to the

areas served by air pick-up.

AAA had planned to expand pick-up service to multi-engine passenger

planes to carry passengers and provide pick-up service to other places.

But fatal crashes in 1944 and 1945 helped end both public and

Congressional support for such an expansion. The Civil Aeronautics Board

denied AAA the permission to expand into the mixed passenger and

pick-up service.

In 1948, the company was awarded a temporary certificate to carry

passengers only if the air mail pick-up lines were terminated. It was

the end for America's last mail-only aviation company and this unique

service was discontinued the next year. The president of AAA, Robert M.

Love, realized the future of the company lay in passenger transport. He

purchased DC-3s from the Army and refurbished them for passenger

traffic. Later that year, All American Aviation became All American

Airways , a passenger airline which operated out of National Airport in

Washington, D.C.

For a few months in 1949, All American Airways flew both Air Pick Up out

of Pittsburgh and passengers out of Washington, D.C. Fittingly, the

last pick-up route, on June 30, 1949, from Jamestown, New York to

Pittsburgh was flown by Norman Rintoul, the pilot who had flown the

first pick-up a decade earlier.

The Engineering division of AAA split off from the main company in 1953

and became part of International Controls in 1982. Its pick-up apparatus

technology had been used extensively in aircraft carrier aviation and

even for the recovery of information capsules from satellites. In 1953

All American Airways became Allegheny Airlines. Fifteen years later, it

merged with Lake Central, and in 1972 with Mohawk. On October 28, 1979,

Allegheny Airlines became US Air. In 1989 it acquired Piedmont. Finally,

on February 27, 1999, US Air became US Airways.

Norman Rintoul, who had piloted the first and last pick-up flights for

All American Aviation purchased a Stinson when All American upgraded its

fleet in 1949. Later that year he donated the plane to the

Smithsonian's Air and Space Museum. The Stinson was kept in storage at

the Paul Garber facility in Silver Hill, Maryland until it came to be

displayed at the National Postal Museum in 1993. Visitors are often

impressed with the beauty and grandeur of the Stinson now suspended from

the atrium ceiling. |

This was one of the Airmail pickup sites.

This was one of the Airmail pickup sites.

This was the other, just off Louden Heights Rd.

1947

On the fly airmail service ended when Kanawha Airport opened in 1947

1947

On the fly airmail service ended when Kanawha Airport opened in 1947

Back

|