Murderer’s Baptism

SUGAR CREEK 1950

I

discovered this long forgotten story a couple of years ago while

researching another topic. I read the entire case and thought it

fascinating, but didnt think it entirely useful for the website.

But month after month the story kept returning to my mind like

the scene from an old movie....and so this is the story of two men:

One a little dim, while the other, on the wrong end of life at

the wrong time. Typically it's alcohol and drugs that cause

otherwise average guys to become candidates for the electric

chair, and this was no exception. The difference here....

was the road from Summers Street to the Sugar Creek....

|

THE BEGINNING

Imagine... 150 onlookers by the time the police arrived SO THE CASE GOES TO TRIAL AND BOTH MEN ARE FOUND GUILTY.  ( mostly due to 150 eye witnesses )

Article written by James A. Hill

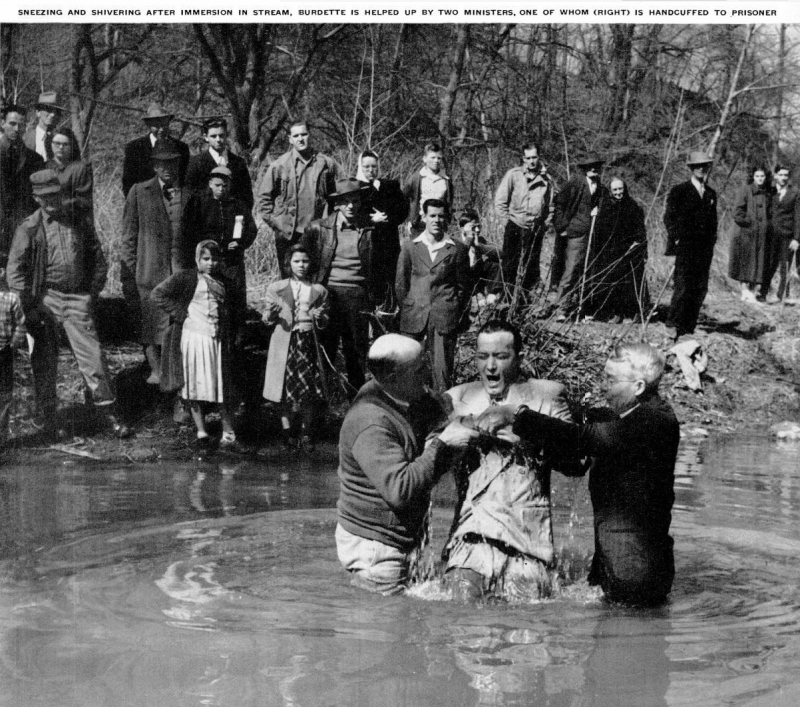

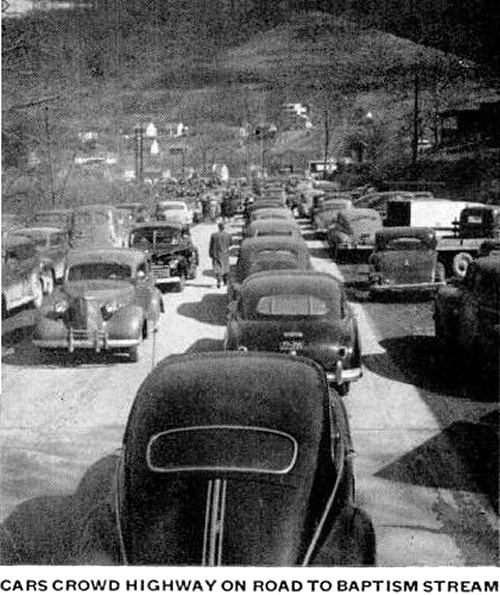

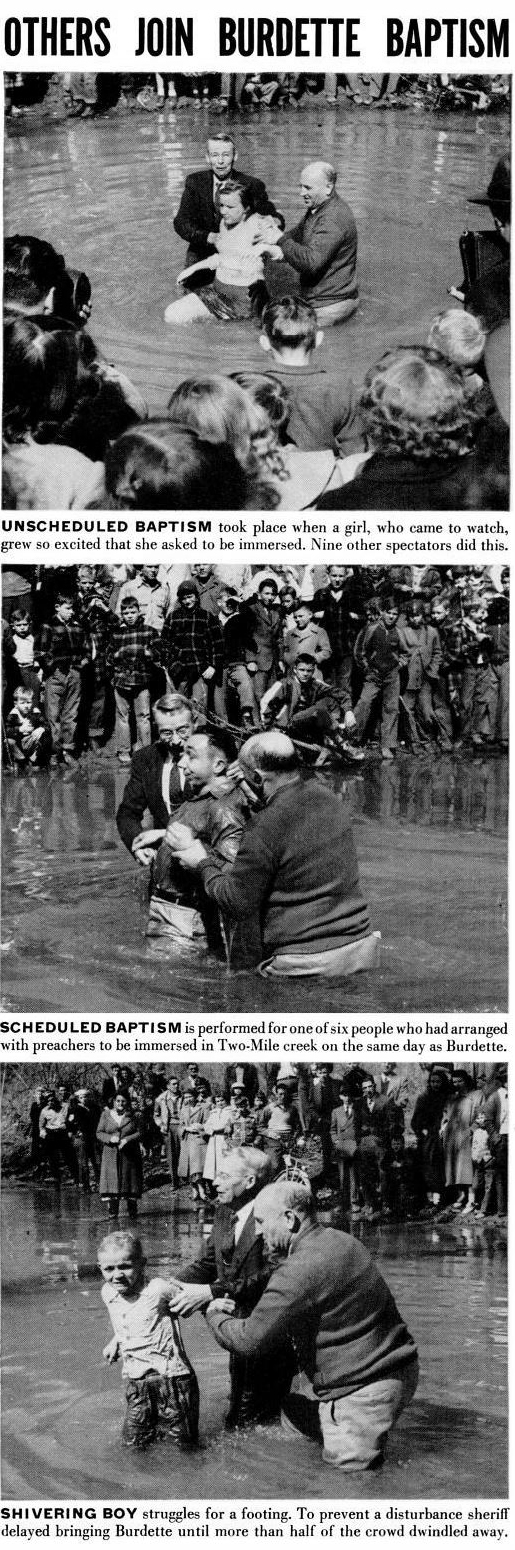

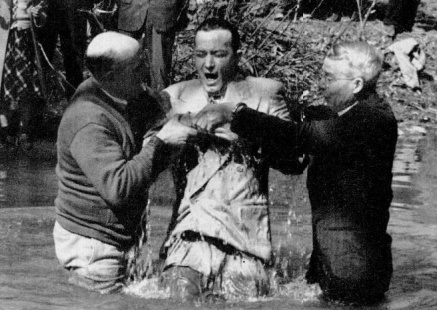

MORE ON THE BAPTISM

Notice the reference to "Elk Two Mile." That should have been "Kanawha Two Mile".Article written by James A. Hill Rt 21 just around the corner from West Washington Street.

Life Magazine

On

March 26, 1951, twenty-six-year-old Harry Atlee Burdette and

thirty-two-year-old Fred Clifford Painter became the first men to be

executed in the penitentiary's electric chair. Both were convicted of

the first degree murder of soft drink salesman Edward C. O'Brien. The

two allegedly stomped O'Brien to death in a Summers Street parking lot

in Charleston around midnight on July 30, 1949. Burdette's attorneys,

former Charleston mayor D. Boone Dawson and D. L. Salisbury, argued

their client had been too intoxicated to have premeditated the murder.

Burdette testified that he and Painter had consumed 4 1/2 pints of

whiskey and nearly a case of beer since 11:00 on the morning of the

incident. Burdette added that he had blacked out the moment the

altercation began and came to in jail the next day. Apparently,

Burdette and Painter had attacked O'Brien to steal a fifth of wine.

Salisbury argued during Painter's trial that his client was legally

insane, due to cerebral syphilis, and that he was under the influence

of alcohol and drugs. In both trials, the juries quickly returned

guilty verdicts against the defendants.

Originally, Burdette's

electrocution was scheduled for April 1950, and Painter's was set for

the following June. Unsuccessful appeals delayed the executions and

Warden Orel J. Skeen set a March 23, 1951 date for both. Shortly after

their convictions, Burdette and Painter were baptized in a creek near

Charleston, and with March 23 being Good Friday, Governor Okey Patteson

stayed the executions until the following Monday. A third man, Robert

Ballard Bailey, was also to be put to death on that day for the murder

of Charleston tavern keeper Rosina Fazio, the mother of Charleston

restauranteur Joe Fazio. On March 22, Patteson commuted Bailey's death

sentence to life imprisonment.

Due to the publicity surrounding

the state's first use of the electric chair, Warden Skeen departed from

tradition and granted reporters interviews with the convicted men one

hour before the execution. After a last meal, Burdette was strapped

into the chair at 9:02 p.m. Following one electric shock, Dr. Charles

A. Zeller pronounced him dead after a period of three minutes and

forty-eight seconds. Guards placed Painter in the chair at 9:10. The

first surge merely knocked him unconscious, requiring another jolt. At

9:19, Painter was pronounced dead. Three separate buttons had been

pushed by prison employees, although only one conveyed current, so

nobody would know who had delivered the fatal shock. Attending the

execution were former Delegate Schupbach and state Senator Robert C.

Byrd. As a sidelight, during the commotion on the day of the

executions, two prisoners escaped from the penitentiary.

|

All photos and articles courtesy of The Charleston Gazette and Life Magazine See Painters Obit HERE At

the September, 1949, term of the Intermediate Court of Kanawha County,

an indictment for murder was returned by the grand jury against Harry

Atlee Burdette and Fred Clifford Painter. The indictment charged that

the defendants "on the ___ day of July, 1949, in the said County of

Kanawha, feloniously, wilfully, maliciously, deliberately,

premeditatedly and unlawfully did slay, kill and murder one Edward C.

O'Brien against the peace and dignity of the State." On the 6th day of

December, 1949, Burdette, then represented by counsel, entered a plea

of not guilty and, each of the defendants having demanded a separate

trial, and the State having elected to first try Burdette, a jury was

impaneled and duly sworn to try Burdette. The trial continued until the

9th day of December, 1949, on which day the jury returned the following

verdict: "We the Jury find defendant guilty as charged of 1st degree

murder without recommendation." After overruling a motion to set aside

the verdict, the court, on the 15th day of December, 1949, entered

judgment against Burdette in accordance with the verdict, that he "be

punished with death", on the 14th day of April, 1950, by electrocution.

On March 14, 1950, Burdette filed in the Circuit Court of Kanawha

County a petition praying for a writ of error and supersedeas to the

final judgment of the Intermediate Court of Kanawha County, and on

March 20, 1950, the circuit court denied the prayer of the petition.

This Court granted a writ of error and supersedeas on the 28th day of

March, 1950, to review the action of the circuit court. Painter was

later tried under the indictment mentioned above, found *73 guilty by a

jury, sentenced to death, and this Court granted a writ of error and

supersedeas to the final order of the Circuit Court of Kanawha County

refusing to review the action of the Intermediate Court of Kanawha

County, and the decision of the Court in that case is rendered

contemporaneously herewith. See State v. Painter, W.Va., 63 S.E.2d 86.

On

Saturday, July 30, 1949, just before midnight, a fight wherein

Burdette, Painter and O'Brien were involved, resulted in the death of

O'Brien. This fight occurred on or near the westerly side of Summers

Street in the City of Charleston, between Lee Street and Washington

Street. The Greenbrier Theatre, fronting on Lee Street, is situated

southerly from the place of the fight, and a large dwelling is situated

immediately north of the rear of the theatre. The easterly wall of the

dwelling extends practically to the edge of the westerly sidewalk of

Summers Street. Immediately north of the dwelling, toward Washington

Street, is an automobile parking lot. There is an entrance to the

dwelling on the side thereof next to the rear of the theatre building,

and another entrance thereto on the side thereof next to the parking

lot. The Stevens Beauty Shop is located in this dwelling, and Alice

Cobb, a girl friend of O'Brien, occupied rooms therein. Apparently the

fighting commenced on the parking lot near the entrance to the

residence, and continued to the sidewalk along the easterly side of the

residence. On the opposite side of Summers Street an alley intersects

that street at right angles and extends in an easterly direction toward

Capitol Street. A store mentioned in the evidence as The Curtain Shop

is located in a building which fronts on Lee Street and extends along

the easterly side of Summers Street to the alley. The record does not

disclose the distance from either Lee Street or Washington Street to

the place where the fight occurred, but the distance from Lee Street

was probably about 100 feet and further from Washington Street.

On

Saturday, July 30, 1949, at about 11:45 P.M., O'Brien got out of a

taxicab near the rear of the Curtain Shop on the easterly side of

Summers Street, near where the alley intersects Summers Street, the

taxicab being headed toward Washington Street, and, while paying the

taxi fare, was asked by either Burdette or Painter if he wanted to

purchase a newspaper. O'Brien answered in the negative and, after

having paid the taxi fare, went around behind the taxi and started

across Summers Street. Burdette or Painter then asked Beaver, the taxi

driver, if he wanted to buy a newspaper, to which Beaver replied that

he "had no use for a paper". Beaver then backed his taxi into the

alley, turned and drove toward Lee Street. After Beaver had turned the

taxi toward Lee Street he heard loud voices, looked back out of his

taxi, and testified that "They just got across the street and about

that time I seen some kind of scuffle and then some people come up and

it was shadowy and I couldn't see very well."

O'Brien,

thirty-one years of age, single, five feet six inches tall, weighing

about 175 pounds, was an employee of the 7-Up Bottling Company,

Charleston, West Virginia, and had driven a truck for that company the

day of the homicide. He worked until about five P.M., went to his home,

took a bath and had his evening meal. About six-thirty P.M. he left his

home, "jolly" and "in a good frame of mind". He was observed by Charles

Lightner, a city policeman, about twenty minutes after six P.M., at the

corner of Washington and Summers Streets, and nothing unusual was

noticed about his actions or demeanor. Between eight and eight-thirty

P.M. he went to the Monarch Beer Parlor and remained there until about

nine P.M. He then went to the "VFW" Club and remained there until about

eleven-forty-five P.M. At about eleven or eleven-thirty he telephoned

Alice Cobb, his girl friend, who had a room in the residence above

mentioned, obtained a date with her and was requested by her to bring a

Sunday morning newspaper and "a drink of wine". He then called a

taxicab and left the club in five or ten minutes. Frank Beaver, the

taxi driver who answered the call, testified that he drove O'Brien to

"about 29 Clendenin Street" and that O'Brien went inside and stayed

"two or three or four minutes". It was testified to *74 by John Moore

that he, John Moore, operated a "bootlegging business" at 29 ½

Clendenin Street, but there was no showing that O'Brien bought a bottle

of wine at the time he was there. Beaver further testified that at the

request of O'Brien he drove to the Greyhound Bus Station on Summers

Street, that O'Brien went into the station, and that he believed

O'Brien made a purchase there; and that he drove O'Brien to the rear of

the curtain shop mentioned above. This witness, as well as the other

witnesses who were in contact with O'Brien the evening before the

fight, testified that O'Brien was sober and was in a good frame of

mind. One witness, Lawrence Westfall, testified that O'Brien drank "Two

Tom Collins" during the two hours he was in the VFW Club, but that when

O'Brien left the club he was sober and "In a good humor".

Burdette

and Painter were residents of Charleston, were close friends, and "when

not working they were out together a great deal". Neither had been

regularly employed for some time. Burdette at time of trial, was

twenty-seven years of age, married, and the father of three children.

On the morning of July 30, 1949, at about ten-thirty A.M., Burdette and

Painter met at a pool room on Summers Street, and remained there until

about nine-thirty that evening. Burdette was asked: "Q. Were you there

continuously all that time?"; and he answered "A. Yes sir." He was also

asked "Q. During the time you were there what did you do?", to which he

answered "A. We drank whiskey and beer and shot pool, is all we done."

At about nine-thirty that evening they left the pool room and went "to

a bootleg joint" on Reynolds Street, "Just long enough to purchase a

pint of whiskey." They then went to the Smith beer garden and "drank

beer and whiskey". At about eleven-forty-five P.M. Burdette and Painter

were back on Summers Street, near the office of the Skyline Cab

Company, and left there, going toward the rear of the Curtain Shop,

apparently reaching the rear of the building housing that shop at about

the time O'Brien arrived there in the taxi driven by Beaver.

There

is conflict in the evidence concerning the acts of Burdette and Painter

in the commission of the homicide as to whether either used a knife in

preventing interference in behalf of O'Brien and as to whether they, or

either of them, were intoxicated to such a degree as to render them

incapable of premeditation. Inasmuch as Burdette and Painter were

acting together in the matter, the evidence as it relates to each

should be stated. Witnesses for the State who saw some part of the

fight will be first considered.

Myrul Burroughs, Gerald

Burroughs and Grover Simmons, acquaintances of O'Brien, on their way to

the midnight show at the Greenbrier Theatre, were walking along the

westerly sidewalk of Summers Street, near the parking lot, at about

eleven-fifty P.M., and saw O'Brien fall from the parking lot to the

sidewalk, and saw Burdette and Painter follow him immediately. They

stated that O'Brien got back on his feet and that Burdette and Painter

continued striking him, and that they, the three witnesses, undertook

to interfere in the fight, to stop it, but were prevented from doing so

by Painter, who threatened them with a knife. Myrul Burroughs testified

that when he saw O'Brien fall O'Brien had a newspaper in his hand, and

that he did not have a knife; that Painter came toward him and said "he

would cut my (witness) guts out". This witness further testified that

Burdette knocked O'Brien down "and started stomping him", and stomped

him about the face. Gerald Burroughs further testified that he saw

Burdette and Painter strike O'Brien and that when he, Myrul Burroughs

and Grover Simmons "started to pull them off they started to fighting

and cussing * * *", and that "The next thing I knew Fred Painter was

striking me with a knife", and when "Painter came at me with the knife

I started backing away and I seen Burdette stomping" O'Brien "in his

face and throat." He also testified that O'Brien had no weapon; that he

saw O'Brien use his hands only to protect his face; that Burdette and

Painter handled themselves "pretty well", and had no difficulty in

staying on their feet, and when asked whether Burdette had any

difficulty when he was stomping O'Brien, replied "None at all"; and

that he thought Burdette and Painter *75 knew what they were doing.

Grover Simmons testified to the effect that Burdette and Painter were

striking O'Brien with their fists; that he did not see O'Brien do

anything "only try to protect his face", and when asked "Did you hear

them say anything about cutting somebody?", answered "Yes, I heard them

say they would cut him"; that after Burdette knocked O'Brien down he

stomped him three or four times, about his face and throat; that he,

Myrul Burroughs and Gerald Burroughs tried to stop the fight; that

Painter had a knife and was "trying to keep the people back"; that he

did not see O'Brien have any weapon; that he saw Painter hit O'Brien a

few licks and also stomp him; and that after Burdette stomped O'Brien

Burdette and Painter "changed hands with the knife" in holding the

bystanders back. He made the following answers to questions asked him:

"Q. As to Harry Burdette, I wish you would describe his actions there

with reference to how he handled his hands and feet during that fight.

A. It seemed to me he knew what he was doing. He knew the way to keep

his balance. He had perfect balance. Q. Did he side step any? A. He did

when he hit Eddie (O'Brien) the last time. Q. Did you see Painter

stagger at any time? A. No, sir." These three witnesses also testified

concerning a bottle being thrown at O'Brien by either Burdette or

Painter, the bottle being broken, and of the contents thereof smelling

like alcohol.

Mrs. Acie Neal, who lived at the residence above

mentioned, shortly before midnight heard someone say "If that is the

way you want to fight, go ahead and cut him."; that she went out of the

residence, saw someone lying on the sidewalk, thought that it was her

brother, requested someone to go for an ambulance, and stated that

"About that time he (Burdette) was up to me and the guy said `stomp his

God damn brains out'", and that Burdette did stomp O'Brien "about three

times". Alice Cobb, the girl friend of O'Brien, shortly after she

talked with O'Brien over the telephone, heard some loud talking and

cursing and heard Mrs. Neal request someone to call an ambulance, and

heard someone say "Oh, you want to fight with a knife, do you?". She

also testified that she picked up a piece of newspaper by a pool of

blood and later turned it over to an assistant prosecuting attorney.

Robert Crouse, a former police officer of the City of Montgomery, saw

Burdette beating O'Brien and testified that O'Brien was merely

protecting himself, "was drooping a little bit like a man out of breath

and like he was all in"; that Burdette knocked O'Brien down; that he,

the witness, told Burdette and Painter to turn O'Brien loose and that

Painter replied "I will cut your God damned heart out"; that after

O'Brien was down and after making the above quoted statement, Painter

kicked O'Brien, and then he, the witness, "started running for the

police". Paul Arthur testified that he saw O'Brien fall to the sidewalk

and a newspaper fell from his hand; that O'Brien got up, tried to

protect himself, was knocked back down, and Painter "straddled him and

he came down on him with his feet"; that Burdette and Painter "seemed

to be holding back the crowd", with what he believed to be a knife; and

that he "was impressed very much that the two men were drinking."Noble

Adkins testified to the effect that he saw Burdette hit O'Brien; that

he ran across the street to the Pure Oil Station to call the police;

that when he got back to where the fight was going on O'Brien was

knocked down; that he started to help O'Brien and was warned by two

boys who were with him "* * * not to go in it", and that both Burdette

and Painter "stomped the man lying on the sidewalk". Robert McCormick

testified that he saw part of the fight, saw O'Brien knocked down, and

that Burdette cursed him and started at him. Thereon Stone saw O'Brien

down on the sidewalk; saw Painter kick O'Brien at least twice in the

upper part of the body. He also testified that a woman requested him to

"come over there quick, that somebody was killing her brother", and

that he saw a knife on the sidewalk. E. D. Smith, a city policeman,

arrived shortly after the fight was over, saw O'Brien lying on the

sidewalk, a lot of blood on the sidewalk, and testified that he

arrested Burdette and Painter. He also testified that Painter was drunk

and that Burdette had been drinking; that *76 Burdette did all the

talking, and that Burdette "told Painter to keep his mouth shutthat he

didn't do it", and that he took a pint of whiskey off of Painter. Roy

Johnson, who had been a member of the city police force for about seven

months, arrived at the scene shortly after the fight, saw Burdette and

Painter standing sixteen or eighteen paces from the body, and testified

that Burdette said to the witness: "The son-of-a-bitch drawed a knife

on me and he got what he deserved. You had better go down and help

him", and that Painter called the witness "A damned rookie cop." This

witness picked up a knife which was partly open and was lying about

eighteen or twenty feet from the body of O'Brien, and also took another

knife from the right hand front pocket of Painter. When asked his

opinion as to whether Burdette and Painter were drinking, he answered:

"Well, my opinion is Painter was drinking enough that he was

staggering, that is mostly weaving. It wasn't too much of a stagger.

Burdette's eyes were glassy but he could talk clearly. I just think he

was drinking is all. Leonard Cunningham, also a city policeman,

testified that he had known Burdette for about fifteen years; that he

saw Burdette and Painter at the scene of the homicide; that Burdette

knew him and told him what had happened; that Burdette told Painter to

be quiet, and that it was not necessary to help Burdette get into the

patrol wagon. Jesse Workman, a sergeant in the city police department,

thought that Burdette and Painter were drinking, but thought they knew

what they were doing, and stated that Burdette seemed "to know what he

was talking about." Dewey Williams, a captain in the Charleston Police

Department, was present when Burdette and Painter were brought into

police headquarters after the fight and testified that Burdette argued

with the patrol driver about keeping some money and that Burdette

seemed to know where he was and what he was doing. Charles Lightner, a

city policeman, saw Burdette and Painter at Smith's Cafe at 108

Washington Street, East, a few minutes before eleven P.M. on July 30

and there talked with Painter and, in answer to a question, stated: "As

far as I could tell they were not drunk.", and that he did not arrest

either of them. Jarrett Hunt, an employee of the Skyline Cabs and whose

duties were "Loading the cabs and marking the drivers in and out" and

who was personally acquainted with Burdette, Painter and O'Brien, saw

O'Brien about nine-thirty P.M. and testified that O'Brien was not

drinking at that time; that he saw Burdette and Painter a short time

before twelve o'clock and that they were then "pretty well loaded", but

that they knew him; that when he tried to get them to get into the cab

to prevent them from being arrested they said, "Jarrett, we like you

but not that much. You tend to your business and we will tend to ours."

He also testified that Burdette and Painted walked to the corner of Lee

and Summers Streets and that they "did not require any assistance to

keep them from falling or staggering." Mrs. Macie Ingraham heard

Burdette say that "he could whip anybody without a knife". A brother of

O'Brien testified that he roomed with him at his mother's home; that he

was familiar with the personal belongings of Edward O'Brien and that he

knew that Edward O'Brien did not carry a knife or ever have one in his

possession.

The State introduced a photograph showing the

residence mentioned above and the immediate surrounding vicinity. Also,

certain evidence as to a newspaper picked up at the scene of the

homicide was permitted to be introduced in evidence, over the objection

of the defendant. K. V. Shanholzer, a chemist and a member of the

Department of Public Safety of the State, from an examination of the

shoes and clothing worn by Burdette and Painter at the time of the

homicide, and from a chemical analysis, determined that there were

human blood stains on the shoes of both Burdette and Painter, and on

the trousers and shirt of Painter. These articles of clothing were

exhibited to the jury; also the shoes, trousers and undershirt worn by

O'Brien at the time of his death were exhibited to the jury.

Dr.

Freeman L. Johnson examined O'Brien after he was removed to the

hospital, found that he was then dead, and that he *77 was bleeding

from the nose and both ears, and "we felt he had a fractured skull, but

that was not ascertained definitely at that time."

J. G. Bane,

who embalmed the body of O'Brien, found "bruises about the face, neck

and legs" of O'Brien. Dr. Benjamin Newman, a pathologist, examined the

body of O'Brien and "found two lacerations of the skull over the right

eyebrow. There were abrasions of the skull, nose, skin and chest. That

was just superficial. When I examined the head I found that there were

hemorrhages on both sides of the head. They were over his ear to what

we call the temporal region. There were hemorrhages of the muscle under

the skin of the forehead. When I examined O'Brien I found a mass of

hemorrhage on the left side which I call a left subdural hemorrhage;

that is, over the coverings of the brain, extending to the very end,

and adjacent there was a contusion which was bruised and hemorrhagic. *

* *. There was a fracture of the base of the skull on the right side.

An examination of the remainder of the body showed an edema but there

were no other fractures I could see. * *. The cause of the death was

the injury to the brain and the severe hemorrhagethe subdural

hemorrhageand the swelling of the brain." This witness further

testified that, in his opinion, "It is impossible to explain all those

lesions or injuries with one blow. The only way I could say is that it

was from several blows."; that the injury was a "dull type of injury.

The trauma was dull.", and that he believed "the basal skull fracture

was additional to the hemorrhage."

The following witnesses

testified on behalf of the defendant Burdette. Oliver Parkins was

walking along the westerly side of Summers Street, near the scene of

the fight, and saw O'Brien "step on the walk and have a knife in his

hand. He said something in a swearing manner, I don't know what it was,

to Harry Burdette and Painter on the parking lot. Painter was reaching

in his breeches' pocket for a knife. I heard him ask Harry for a knife

and Harry said he didn't have one. I saw him strike the man a couple of

times and he fell on the sidewalk. The boy laid there just a second and

he started to get back and Harry swung at him some pretty hard blows

and Harry hit him some more and the boy fell again. When he fell this

time his head hit the sidewalk."

Carl Seavers, an acquaintance

of Burdette and Painter, appeared at the scene after O'Brien had been

knocked to the sidewalk the last time, and testified that he heard one

of the officers ask Burdette "Why didn't you run so I could shoot

you?", to which Burdette answered that "he (Burdette was a fool but he

wasn't that big a fool." This witness saw the officer pick up the knife

and stated that it was five or six feet from the body of O'Brien, and

also heard Burdette make a statement to one of the officers that

"anyone who drew a knife on him would be sorry". He identified the

knife found at the scene as one he had seen at the home of Burdette

about June 15, 1949. He also stated that both Burdette and Painter were

drunk. Russell Guy Harrison testified that he had known Burdette and

Painter for several years, was with them the evening of the homicide

from about seven P.M. until about ten P.M. He testified that he first

got with Burdette and Painter at the Club Pool Room and stayed there

until about nine P.M. That the three of them then went to "a beer

joint" on the lower end of Washington Street, near the bridge; that

they stayed there drinking beer until about ten P.M.; that they then

went over and "bought a pint of whiskey", then "went from one beer

joint to another beer joint"; that the three of them got in the car of

the witness and, after driving around for some time, Burdette and

Painter got out of the car near the Skyline Cab stand, on Summers

Street. He further testified that when Burdette and Painter got out of

his car on Summers Street "they couldn't hardly get out of itthey was

so drunk." This witness further stated that on that evening he took

Burdette's knife from Painter, that he asked Burdette to let him keep

the knife, and that Burdette said "No, he would keep it".

Clyde

Legg testified that he saw Burdette and Painter at the "beer joint on

*78 Washington Street; that he stayed there from about nine-thirty P.M.

until about ten-thirty P.M., and that Burdette and Painter were there

when he left; that they were "drinking rapidly", drinking "beer and

whiskey". He further stated that in his "estimation they were strictly

drunk. They started to dance and stagger around." George Legg, a

brother of Clyde Legg, was at the beer joint at the time Clyde was

there. He stated that in his opinion Burdette and Painter were drunk.

Harry Helmick saw Burdette and Painter in the "beer joint" from

eight-thirty P.M. to nine-thirty P.M., and stated that they were drunk.

Gerald Wilman saw Burdette at Smith's Cafe, 108 Washington Street,

about nine P.M., and stated that Burdette was "plenty drunk". Aileen

Burdette, wife of Harry Atlee Burdette, saw her husband sometime during

the day of July 30 at the "Club building", and states that "He was

awful drunk. I tried to get him to go home with me and he wouldn't do

it." Ruth King testified that she saw O'Brien fall to the sidewalk, get

up and start striking at Burdette; that "Burdette hit O'Brien and he

didn't get up anymore" and that she thought the parties fighting were

drunk. Edith Harrell came down Summers Street about the time the fight

started, but the only evidence given by her which could be considered

material is shown by the following question and answer: "Q. Did you see

any of this trouble between Burdette and Painter and the O'Brien boy

that night? A. I didn't see no trouble only when Harry was standing on

the street. He came across and started to draw a knife, and Harry said,

"I will strike any man that draws a knife on me.'"

Fred C.

Painter testified in behalf of Burdette. He stated that he was thirty

years of age; that he had known Burdette for about eight years; that on

the day of the homicide he first saw Burdette "at the Club on Summers

Street" about eleven A.M.; that they stayed at the Club until nine or

nine-thirty that evening; that they then, together with the witness

Russell Harrison, went to 108 East Washington Street; that he does not

remember how long they remained there, but does remember going back to

Summers Street. He further testified that he and Burdette statrted

drinking at about eleven-thirty in the morning and continued to drink

beer and whiskey the rest of the day, and that they bought and drank

five pints of liquor, except that they gave drinks to their friends;

that he bought eight "yellow jackets"; that to the best of his judgment

he took four of them and Burdette took the other four, "at the pool

room during the afternoon". He testified further that he did not

remember where he went after he came back on Summers Street, but did

remember "something of a commotion on Summers Street"; that he got

three scratches; that he owned no knife; and that he recalled "somebody

hollering about a knife". "I went all to pieces" and "didn't know

anything until the next day".

Burdette testified in his own

behalf, and stated that he went to the Club poolroom around ten-thirty

A.M., July 30, 1949, and that he and Fred Painter were there until

about nine-thirty that evening; that they then went to a bootleg joint

on Reynolds Street and purchased a pint of whiskey; that they then went

to the Smith beer garden and stayed there around two hours; that he

remembers going to another beer garden and being back on Summers

Street, near the Skyline Cab Company office, trying to purchase a

paper; that he and Painter "walked out to the corner and there some

argument started. Painter went across the street and he hollered for me

and I went over there. This boy was trying to cut us both with a knife

and we backed off clear into that parking lot"; that "He backed us up

in the parking lot and I seen I couldn't get away from him and I had to

fight him. I don't remember hitting him," that he was aware of the

knife and that "the knife was the first thing that seemed to scare me

so", and that after the fight was over he "was in a sort of daze." He

further testified to the effect that the knife taken from Painter's

pocket was owned by him; that he did not use the knife in fighting

O'Brien; and that he and Painter drank four pints of whiskey that day

and a bottle of beer about every half hour while at the pool room. When

*79 asked if he was drunk he replied: "Yes, sir, I was drunk, but when

I saw the boy with the knife it sobered me up. When he backed me

against the parking lot I had to fight him as well as I could. I went

as far as I could on the parking lot and when I was fighting the boy I

blanked out and the next thing that happened I was against this

building and then the `law' came."

A statement made by Burdette

after his arrest and before "breakfast time the next morning",

witnessed by officers S. N. Rutherford and D. E. Williams, was admitted

as evidence. Burdette admits signing the statement, but says of the

statement that "there is a lot of things that is not right". In so far

as appears to us to be material, the statement reads: "I, Harry Atlee

Burdette, make the following voluntarily signed statement * * *. No

threats or promises have been made to me and I know this statement can

be used as evidence in a court of law.

"I left home Friday July

the 29th around 6 o'clock in the afternoon. I came to Charleston and

stayed down in Charleston Friday night. I got up about noon July 30th,

1949. I loafed and played pool at the Club pool room on Summers Street

until near midnight. While I was playing pool I drank a few bottles of

beer. * * *.

"Fred Painter drank about the same amount of beer

that I did * * *. Fred Painter and I left the Club Pool Room together

and started home, walking north on Summers St. * * *. I bought a Daily

Mail and Charleston Gazette paper, after we had crossed Lee Street,

walking north on eastern side of Summers St. About the midway between

Washington and Lee Sts. a man standing on opposite side of Summers

Street yelled at me and wanted a paper. I told him I didn't have any

papers to sell; that I had bought the papers to take home, and he

started to raise hell and started to calling me names. Fred Painter and

I walked across the street to where the man was standing, and the man

pulled out a knife and started cutting at me. I dodged him and just

kept hitting him. I didn't let up. I don't know what happened to his

knife but I know when the policemen came they found his knife. I know

Fred Painter didn't hit him but while I was fighting with him some

other men started to interfere and I think Fred Painter kept them from

taking any part in it. I hit this man several times before I knocked

him down. * * *. As far as I know I never saw this man before * * *.

"I

have read the above statement consisting of three pages written in

pencil on yellow paper, and swear it is true and correct, * * *." It

will be noted that certain parts of this statement do not accord with

the statements made by Burdette on the witness stand or with certain

other evidence offered in his behalf.

We think it clear from the

evidence that the jury and the trial court were justified in believing

that Burdette and Painter were the aggressors throughout the fight;

that the assault made by them upon O'Brien was vicious, brutal and

continued over a considerable period of time; that after O'Brien had

been knocked to the sidewalk the last time by Burdette, both Burdette

and Painter continued to kick O'Brien about the head, with such force

as to probably produce death, one kicking while the other, by the use

of the knife, prevented interference from bystanders who attempted to

stop the fight; that both Burdette and Painter were aware of their

actions, were capable of forming intentions, and of premeditation, and

that O'Brien died as a result of the continued and repeated blows

administered him by Burdette and Painter. There can be little doubt

that both Burdette and Painter had, on the day of the homicide, drunk

intoxicating liquors to some extent, but it seems clear also, and at

least a jury was warranted in finding, that at the time of the homicide

Burdette and Painter were capable of acting maliciously and with

premeditation. If the evidence of the State is believed, which the jury

had the right to do, the joint actions of Burdette and Painter were

timely coordinated; they recognized persons with whom they were

acquainted, talked intelligently, had no difficulty in staying on their

feet, and handled themselves throughout the fight without any

noticeable staggering, *80 even while repeatedly kicking O'Brien about

the head.

The actions of the trial court complained of are

included in the following propositions: In overruling the demurrer to

the indictment and in denying the motion to quash the indictment; in

refusing to grant Burdette's motion for a continuance; in refusing to

grant a new trial because of after discovered evidence; in refusing to

set aside the verdict and to grant Burdette a new trial because not

supported by the law and the evidence; in giving certain instructions

on behalf of the State, and in refusing to give certain instructions

offered by Burdette; in permitting the jury to consider certain

evidence offered by the State; in permitting the assistant prosecuting

attorney to argue that robbery was a motive for the killing; and in

that the punishment imposed upon Burdette constituted cruel and unusual

punishment.

We think the indictment is in sufficient form.

Nothing is pointed out by defendants as to why the demurrer thereto

should have been sustained, or why the indictment should have been

quashed, except it is shown that one of the grand jurors was not a

resident of Kanawha County. Code, 62-9-3, provides that an indictment

for murder shall be sufficient if it alleges, in effect, that the

defendant, at a time designated, in a certain county, "feloniously,

wilfully, maliciously, deliberately and unlawfully did slay, kill and

murder one B.........., against the peace and dignity of the State." An

indictment substantially following the form provided by the statute is

sufficient. State v. McMillion, 104 W.Va. 1, 138 S.E. 732.

One

of the qualifications of grand jurors set out in Code, 52-2-2, is that

they "shall have been bona fide citizens of the State and county for at

least one year immediately preceding the preparation of the list" of

grand jurors prepared by the jury commissioners. Code, 52-2-12,

provides that "No presentment or indictment shall be quashed or abated

on account of the incompetency or disqualification of any one or more

of the grand jurors who found the same." Under this section a question

as to the incompetency or disqualification of a grand juror can not be

heard for the purpose of having an indictment invalidated. State v.

Austin, 93 W.Va. 704, 117 S.E. 607; State v. Driver, 88 W.Va. 479, 107

S.E. 189, 15 A.L.R. 917. Of course this rule would not apply where

fraud or corruption is charged. State v. Carter, 49 W.Va. 709, 39 S.E.

611.

There is no merit in the contention of the defendant that a

continuance should have been granted him by the trial court. The motion

therefor was grounded upon the fact that Harold Teague, for whom

Burdette had caused a subpoena to be issued, but not served, was absent

at the time of the trial. We are of the opinion there was not a

sufficient showing that the testimony of the witness was material, that

it was not merely cumulative, or that it would probably be produced at

a future trial. It clearly appears that the evidence of the witness

would have been merely cumulative. Granting of continuances by trial

courts are matters within the sound discretion of such courts. Here

that discretion was not abused. See State v. Lucas, 129 W.Va. 324, 40

S.E.2d 817; State v. Whitecotten, 101 W.Va. 492, 133 S.E. 106; State v.

Bridgeman, 88 W.Va. 231, 106 S.E. 708.

The motion for a new

trial upon the ground of after discovered evidence was based primarily

upon an affidavit of Frank A. Blum, Jr. It appears from this affidavit

that Blum is a resident of Pennsylvania; that he was walking along

Summers Street at the time of the fight and that he would testify to

the effect that "between five and eight men were engaged in the fight"

and that they seemed to be considerably intoxicated; that he saw

O'Brien have an open knife during the course of the fight and heard

Burdette say, "I know he has a knife"; that Burdette struck O'Brien a

hard blow, knocking him to the sidewalk with great force, and that

Burdette then ran in and kicked him; that Painter also ran in and

kicked O'Brien twice, and that he is positive that "no woman * * *

picked up O'Brien's head and held it in her lap * * *." *81 This

evidence being merely contradictory and probably not sufficient to

produce a different result at a new trial, it was not error for the

trial court to refuse to grant a new trial based thereon. It is very

significant that Blum did testify in the case of State v. Painter,

supra, and that the verdict in that case was guilty of murder in the

first degree without any recommendation. In State v. Beckner, 118 W.Va.

430, 190 S.E. 693, Point 1 of the syllabus, this Court held: "On a

motion for a new trial on the ground of after-discovered evidence, any

showing in support thereof must disclose, not only diligence to

discover such evidence before trial, but that the same is calculated to

produce, and would support, a different verdict from that returned by

the jury."

See State v. Porter, 98 W.Va. 390, 127 S.E. 386;

Edwards v. Keifer, 92 W.Va. 650, 115 S.E. 838; and Sisler v. Shaffer,

43 W.Va. 769, 28 S.E. 721.

The position of the defendant as to

the insufficiency of the evidence to support the verdict of murder in

the first degree is based primarily upon the contention that Burdette

was so intoxicated that he was incapable of deliberation and

premeditation immediately before or during the time of the fight. The

duty of proving deliberation and premeditation, of course, is upon the

State. State v. Williams, 98 W.Va. 458, 127 S.E. 320. Malice or

premeditation need not exist for any great length of time before the

homicide. It was held in State v. Porter, 98 W.Va. 390, 127 S.E. 386,

Point 9, syllabus, that: "It is well settled that, if intent to take

life is executed after deliberation and premeditation, though but for a

moment or an instant, the crime is murder in the first degree."

Ordinarily

malice can not be inferred from blows with the fist, but such an

assault may be accompanied with such brutality and violence that malice

and premeditation will be implied. In State v. Roush, 95 W.Va. 132, 120

S.E. 304, Point 6, syllabus, this Court held:

"A malicious

intent to kill cannot be presumed from the striking of a full-grown

person on the head with the bare fists by a person of small stature and

mediocre strength, although death results, unless the assault is so

vicious, continued, deadly, and barbaric, and under such circumstances,

that malice can be implied."

There can be no doubt here that the

jury was justified in concluding that the killing of O'Brien was done

with malice, deliberation and premeditation. The assault was vicious,

brutal and continued by both Burdette and Painter, even after O'Brien

was helpless, as disclosed by the evidence of many witnesses, some of

whom testified on behalf of the defendant, Burdette. The assault was

not merely with the fists. After O'Brien was knocked down and unable to

defend himself, Burdette said he would "* * * stomp his God damn brains

out", and both Burdette and Painter did repeatedly stomp him, and after

the police arrived Burdette said: "The God damned son-of-a-bitch got

what was coming to him." In such circumstances the defendant must be

presumed to have intended the immediate, direct and necessary

consequences of his acts. State v. Roush, supra. In State v. Farley,

125 W.Va. 266, 23 S.E.2d 616, Point 1, syllabus, this Court held:

"Deliberation and premeditation are elements of the offense of murder

in the first degree, which may or may not be established by inference

according to the circumstances of each particular case."

In

McWhirt's Case, 3 Grat. 594, 595, 44 Va. 594, 595, 46 Am.Dec. 196, the

defendant was indicted, with others, for the murder of Martin, who

abused the son of McWhirt. The killing was by "a use only of fists and

feet", and it was contended by the defendant that no intent to kill was

shown, but that the purpose of the attack upon Martin was chastisement

for the abuse of the son. The Court held that the fact "that

chastisement, and not killing, was intended, will not reduce a homicide

to manslaughter, where the manifest design was to do great bodily

harm", and that the fact that the "killing was produced by the use only

of the fists and feet does not reduce the offense below the rank of

murder, when such use was excessive, cruel and outrageous in nature,

and continuance." The Court, in the opinion, *82 used language very

appropriate here. "It was strongly contended, that chastisement, and

not death, of the deceased, was clearly intended. Malice aforethought

may consist in the intention to do great bodily harm, as well as to

kill; and whether the intention be the one or the other, and death

happen, the law will not surrender its general presumption, that the

homicide is murder. No one can review these transactions without seeing

most clearly that great bodily harm at least was intended to be

perpetrated upon the deceased. Much stress was also laid upon the

circumstance, that the prisoner might have resorted to deadly weapons,

which were at hand, if he had designed any fatal injury to the

deceased; and that, instead of employing these, he had only availed

himself of the weapons which nature had furnished him with. And it was

moreover insisted, that no case had been found deciding the homicide to

be murder, when, under such circumstances, the fatal attack had been

made only with the fists, and the death of the party beaten was not

immediately produced under the infliction of the violence; but followed

some time afterwards. The fists may not, indeed, be regarded generally

as a deadly weapon; but they become most deadly, by blows often

repeated, long continued, and applied to vital and delicate parts of

the body of a defenceless, unresisting man on the ground. And if to the

injury they are capable of producing, when wielded by a strong man, you

add all the accompanying injuries which the more powerful agency of

stamping the party on the ground may inflict, there might be a strong

ground to infer the intention, not merely to cause great bodily harm,

but even death itself. Without dwelling particularly upon the

circumstances, and the degree of the violence under which the deceased

suffered, it can not be regarded otherwise than as excessive, cruel,

greatly exceeding the widest boundaries of mere chastisement,

outrageous in its nature, as well in the manner as the continuance of

it, and beyond all provocation to the offense. And we may apply to it,

with great propriety, the saying quoted above of Lord Holt, `that

barbarity will often make malice.'" Other cases to the effect that

malice and premeditation may be inferred are State v. Roush, supra;

State v. Medley, 66 W.Va. 216, 66 S.E. 358; State v. Young, 50 W.Va.

96, 40 S.E. 334; State v. Douglass, 28 W.Va. 297; Carson v.

Commonwealth, 188 Va. 398, 49 S.E.2d 704; Dawkins v. Commonwealth, 186

Va. 55, 41 S.E.2d 500; Commonwealth v. Lisowski, 274 Pa. 222, 117 A.

794; Maulding v. Commonwealth, 172 Ky. 370, 189 S.W. 251; People v.

Denomme, 6 Cal.Unrep.Cas. 227, 56 P. 98. It seems clear, therefore,

that in the circumstances of the instant case the question of malice

was one for jury determination. State v. Saunders, 108 W.Va. 148, 150

S.E. 519; State v. Hedrick, 99 W.Va. 529, 130 S.E. 295; State v. Young,

supra.

The jury was fully and clearly instructed as to the law

relating to malice, premeditation and deliberation necessary to raise a

homicide to murder in the first degree. In State v. Welch, 36 W.Va.

690, 15 S.E. 419, Point 7, syllabus, this Court held: "The question

whether a particular homicide is murder in the first or second degree

is one of fact for the jury. Where a jury has found the case to be one

of murder in the first degree, as in other cases, the court should not

disturb the verdict, unless the finding of murder in the first degree

be plainly and manifestly contrary to or without sufficient evidence."

Burdette

complains particularly of the action of the trial court in giving to

the jury State's Instructions Nos. 4 and 5, which read as follows:

"State's Instruction No. 4

"The

Court instructs the jury that, if you believe from the evidence in this

case, beyond a reasonable doubt, Harry Atlee Burdette and Fred Painter,

acting together, or the defendant Harry Atlee Burdette by himself,

wilfully, maliciously, deliberately and premeditatedly killed the

deceased, Edward O'Brien, you should find the defendant, Harry Atlee

Burdette, guilty of murder in the first degree, although he may have

been drinking intoxicating liquors before and at the time of the

killing, unless you further believe from the evidence that at the time

of the killing he was so grossly *83 intoxicated that he did not know

he was doing wrong nor did not know what the consequence of his act

might be."

"State's Instruction No. 5

"The Court instructs

the jury that a person who is intoxicated may yet be capable of

deliberation and premeditation; and if the jury believe from all the

evidence in the case beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant,

Harry Atlee Burdette, acting alone or in concert with Fred Clifford

Painter, willfully, maliciously, deliberately and premeditatedly killed

the deceased, Edward C. O'Brien, you should find him guilty of murder

in the first degree although he was intoxicated at the time of the

killing."

Apparently the objection made to these instructions is

that they interpose a defense of insanity where that defense is not at

issue and thus confused or misled the jury. We do not understand

defendant to contend that a person can not be guilty of murder in the

first degree even though that person be intoxicated, if in fact the

person be capable of wilful premeditation and deliberation. The law

seems clearly to be that only where the defendant is intoxicated to

such a degree as to be thereby rendered incapable of forming an intent

to kill, or wilful premeditation and deliberation, will the degree of

homicide be reduced from murder in the first degree, because of such

intoxication. Applying this rule to the instant case, we can not see

where the defendant could possibly have been prejudiced by the giving

of these instructions. They appear most favorable to him. It is

conceivable that he could have known that he was "doing wrong yet not

have been able to form specific intent, or to wilfully premeditate and

deliberate." Instruction No. 4 was given in practically the same form

in State v. Corey, 114 W.Va. 118, 171 S.E. 114, except as to the

wording relating to the insanity involved in the Corey case. In that

case this Court held, Point 3, syllabus: "`A verdict of guilty in a

criminal case will not be reversed here because of error committed by

the trial court, unless that error is prejudicial to the accused.'

State v. Rush, 108 W.Va. 254, 150 S.E. 740."

Under the evidence

in the instant case the question whether Burdette was intoxicated to

such a degree as to be incapable of forming an intent to kill or of

wilful premeditation and deliberation was a question for the jury and,

having been properly instructed by the court in relation thereto, this

Court has no right to disturb their finding. The precise question

involved here was properly presented to the jury by the giving of

Defendant's Instruction No. 30, which reads: "The Court instructs the

jury that though they may believe from the evidence in this case that

the defendant Harry Burdette, killed the deceased without any

provocation and through reckless wickedness of heart, but at the time

he did the act, his condition from intoxication was such as to render

him incapable of doing a willful, deliberate and premeditated act, they

cannot find him guilty of murder in the first degree."

Burdette

also assigns as error the action of the trial court in giving to the

jury State's Instructions Nos. 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7. Instruction No. 1 told

the jury that one of five verdicts could be returned, murder in the

first degree, murder in the second degree, voluntary manslaughter,

involuntary manslaughter, and not guilty, defined each, and informed

the jury as to the punishment provided as to each of such crimes. No. 2

informed the jury as to the presumption of an unlawful homicide being

murder in the second degree, the burden being upon the State to show it

was murder in the first degree, and the burden being upon the defendant

to show it to be without malice, and therefore only manslaughter, or

that he acted lawfully. No. 3 simply informed the jury that the

intention to kill need not exist in the mind of the accused for any

particular length of time prior to the killing to constitute a wilful,

deliberate and premeditated killing. No. 6 dealt with the right of an

aggressor or assailant to rely upon the defense of self-defense, and

No. 7 informed the jury as to the law governing the burden of proof

where self-defense is relied upon as an excuse for the killing.

Defendant's theory of self-defense was correctly stated to the jury in

instructions offered by him. No *84 specific ground of objection is

mentioned in the brief filed in behalf of Burdette as to any of these

instructions and, after careful consideration, we find no prejudicial

error in the giving of any of them.

Burdette also complains as

to the action of the court in refusing to give to the jury his

Instructions Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 17, 19, 21, 25, 26, 27, 31, 32, 33 and

35, but does not assign specific grounds showing the basis of his

objections. No. 1 would have directed the jury to find the defendant

not guilty and the giving thereof would not have been warranted. Nos.

2, 3 and 4 would have instructed the jury that the greatest offense for

which Burdette could be convicted was less than Murder in the first

degree, and the giving of any of them would have been clearly

unwarranted under the evidence, as previously indicated. No. 17 dealt

with reasonable doubt, was covered by other instructions, and as drawn

was incorrect and misleading. No. 19 was amended by the court by

inserting the words "after having heard the instructions of the court,

and argument of counsel", thus requiring the jury to not only consider

the evidence but to consider the instructions and arguments, before

reaching a verdict. There was no error in so amending the instruction.

The other instructions of defendant which were refused were fully

covered by other instructions given, and we find no need for further

discussion of them here.

The complaint of the defendant Burdette

as to the admission of certain evidence over his objection relates to

the introduction of a newspaper supposed to have been the one purchased

by O'Brien. Burdette contends that the introduction of the paper tended

"to prejudice the minds of the jury by reason of its gruesomeness

unfairly against the defendant in this case." Shortly after the body of

O'Brien was removed from the sidewalk Patrol Officer Smith placed three

sheets of a newspaper found near there over the blood spot on the

sidewalk, and a little later Policeman Johnson placed the remaining

part of the paper over the three sheets. Later, Alice Cobb picked up

the paper and kept it in her possession until it was delivered to a

representative of the prosecuting attorney's office. She identified the

paper at the time of the trial as the one which she picked up and as

being dated July 31, 1950, and stated, in effect, that it was saturated

with blood when it was picked up. We see no error in permitting the

jury to have this evidence. The paper was sufficiently identified and

could possibly have been of aid to the jury in determining the

viciousness of the attack. True, it may have had considerable effect on

the minds of the jury, but that is no reason why it should have been

rejected. That objection may be said of almost any material evidence.

See State v. McDonie, 89 W.Va. 185, 109 S.E. 710; State v. McKinney, 88

W.Va. 400, 106 S.E. 894; State v. Henry, 51 W.Va. 283, 41 S.E. 439;

State v. Baker, 33 W.Va. 319, 10 S.E. 639.

Complaint is also

made that the prosecuting attorney, in his opening statement to the

jury, told them that the purpose of the defendant in making the attack

was robbery, and that an assistant prosecuting attorney made a

statement to the same effect in the closing argument. It will be

remembered that there was evidence to the effect that Alice Cobb, a

short time before the fight, requested O'Brien to bring her a drink of

wine; that O'Brien had the taxi make a stop near 29 Clendenin Street,

"a bootleg joint", and that a bottle was thrown, presumably by either

Burdette or Painter, during the fight, and that the contents thereof

smelled like alcohol. The State, however, did not prove that O'Brien

purchased or ever had in his possession a bottle of wine, except

possibly by inference which may be drawn from the above acts and from

the further fact that it was proved that Painter had in his possession

at the time of his arrest the pint of liquor last purchased by Burdette

and himself. Presumably this was the evidence which was referred to by

the prosecuting attorney. We think reference thereto could not have

been prejudicial to the defendant, in view of all the evidence. There

is no attempt to show in what manner the defendant could have been

prejudiced thereby. Moreover, the alleged statements of the *85

prosecuting attorney and of the assistant prosecuting attorney were not

made part of the record. As to this assignment of error, the defendant

below relies upon State v. McLane, 126 W.Va. 219, 27 S.E.2d 604; State

v. Hively, 103 W.Va. 237, 136 S.E. 862; and State v. Moose, 110 W.Va.

476, 158 S.E. 715. These cases, we think, have no application here.

The

defendant Burdette further complains that the sentence imposed by the

trial court is "a violation of Article III, Section 5 of the

Constitution of West Virginia, and of the 8th amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. The point is not argued in the brief

of defendant. We assume that the position of defendant is that

execution of the sentence of death by electrocution constitutes "cruel

and unusual punishment" within the meaning of the constitutional

provisions.

By Chapter 37 of the Acts of the Legislature of

1949, Section 3, Article 7, Chapter 62 of the Code of West Virginia was

amended so that now "The sentence of death shall, in every case, be

executed by electrocution of the convict until he is dead", except in

certain instances not material here. The amendment became effective

March 12, 1949. Prior to that time execution of the death sentence was

required by statute to be "by hanging the convict by the neck until he

is dead". Section 5 of Article III of the State Constitution, in so far

as applicable, reads: "Excessive bail shall not be required, nor

excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishment inflicted. *

* *" The Eighth Amendment to the Federal Constitution is in precisely

the same language.

It seems well settled that punishment of

death by electricity does not constitute cruel or unusual punishment.

It is common knowledge that the purpose and intent of the Legislature

of West Virginia in enacting the amendment to Code, 62-7-3, was to

provide a more humane and less cruel means for execution of death

sentences. That the enactment of the amendment was within the power of

the Legislature can not be doubted. In Ex parte Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436,

10 S. Ct. 930, 34 L. Ed. 519, a case involving a similar question, from

the State of New York, it was held that execution of sentence of death

by electricity is within the sphere of the legislative power of the

State. This case was cited in State v. Woodward, 68 W.Va. 66, 69 S.E.

385, 30 L.R.A.,N.S., 1004. See McElvaine v. Brush, 142 U.S. 155, 12 S.

Ct. 156, 35 L. Ed. 971. The Constitution of Virginia of 1776 contains a

provision to the same effect as the above quoted provision of Section

5, Article III of the West Virginia State Constitution, and the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia, in Hart v. Commonwealth, 131 Va. 726, at

page 743, 109 S.E. 582, at page 587, stated; "The punishment of death

by electrocution (which is the present mode of inflicting the death

penalty in Virginia), as is well settled, cannot in itself be regarded

as a cruel or unusual mode of punishment."

We have carefully

examined the record of this case and are of the opinion that the

defendant, Burdette, has had a fair and impartial trial. He has been

ably represented by counsel in the courts below and in this Court, and

a jury, the trial court and the circuit court, have found him to be

guilty of murder in the first degree, without recommendation. Such

conclusions can not be reached, of course, without much anxiety,

concern and solicitude. Some consolation may be had, however, in the

belief that a reasonably strong enforcement of criminal laws may save

the lives and protect the rights and property of innocent persons.

We

therefore affirm the judgments of the Circuit and Intermediate Courts

of Kanawha County, and remand this case to the intermediate court for

the purpose of fixing a date for carrying the judgment of that court

into effect.

|

Back to index

|