|

The park was developed by

Johnny Denton who owned Gold Medal Shows, a carnival that toured

several states, and I think another one that traveled under his name.

The constant setting up and tearing down eventually takes its toll on

even the best rides and equipment, and it becomes too costly to

continue. In Joyland he must have felt he could extend the life of some

of his aging equipment.

Although Denton was the

primary force behind the park and surely had the biggest stake, he

wasn't the only one involved. Joyland was home to several colorful

entrepreneurs during its brief existance, including Bobby Cooper, Natie

Brown, John Swisher, the Picozzis, the Carters, and the Millers. Each

of these brought their own unique talents and offerings, but only

Cooper, who was in his mid to late twenties at the time, brought both

rides and concessions.

Conley and I started working

at the park at about the same time, and we both worked full time that

first summer. "There were nine of us and we never had much," Conley

recalls. "Times were tough back then and there weren't many jobs

around, so I jumped at the chance to go to work for $3.00 a day." I

worked off and on at the park the next two seasons, but Cooper

persuaded Conley to go to work on a rail carnival for his sister in

Canada, and paid his way to Philadelphia to meet her. Conley recalls

that he spent "the next four or five years on the road, first in

Canada, then back in the states," and adds "I learned more during that

period on the road than I could have learned anyplace else."

By today's standards, the

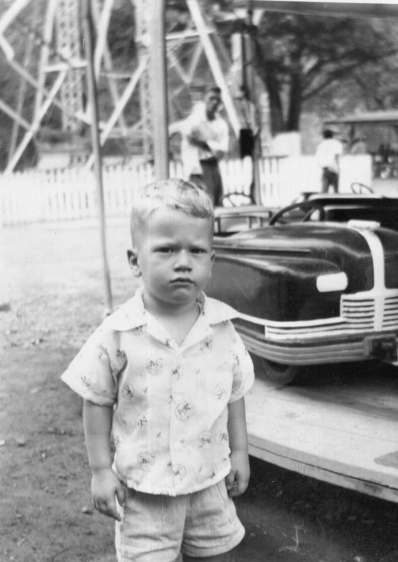

park would be considered small, but at the time it was quite nice.

There were usually six or more full size rides, including the bumper

cars, ferris wheel, tilt-a-whirl, octopus, carousel, and the Joyland

Railroad that nearly encircled the park, plus one or two others that

would be set up from time to time depending on what wasn't needed on

the road. For a while there was even a portable roller skating rink.

There were also numerous kiddie rides including live ponies, and a

roller coaster that always seemed too large for most kids and too small

for most adults.

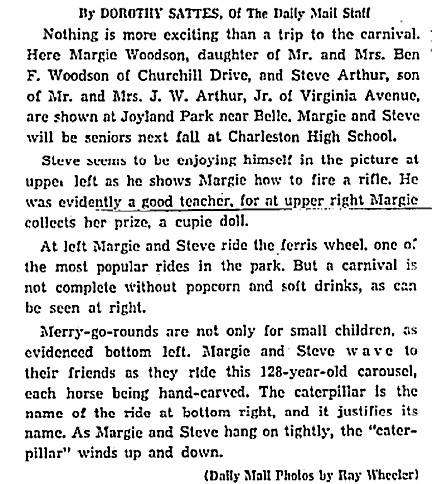

One ride that was truly

memorable was the 150-year-old German made carousel Denton brought down

from Cleveland for the grand opening on May 21, 1955. The Charleston

Daily Mail's Bob Jarrell, in his Roving the Valley article of August 5

that summer, cited ride superintendent Arthur (Dutch) Ream in

describing the ride's 36 horses, that some were "almost as large as a

real pony. All the horses have lifelike glass eyes, something you don't

see nowadays on merry-go-rounds." My younger sister Kathy recalls,

"When I think of Joyland, I always think of the carousel and this one

particular big white horse, my favorite. It was the most beautiful

horse in the world."

***SEE ONE OF THE ORIGINAL HORSE'S BELOW***

I have no idea what the

attendance figures might have been, but the park was often packed and

was particularly popular with students and other young people. Gerald

Terry, a real estate appraiser with Goldman Associates, Inc. in

Charleston, remembers the free rides and sodas he earned at Joyland.

"They had a policy of rewarding students with free drinks and rides for

each "A" on their report cards. I always made good grades so I'd go and

get several free things." Darrell Daniels, news director at WQBE,

remembers the park as a great place to meet friends and hang out on

weekends, "I've got some wonderful memories of Joyland. As a student I

didn't have much money to spend, but it was great to be able to get

together with friends in a wholesome atmosphere."

Among Joyland's favorite

offerings were the concessions, including various snack bars as well as

games of both skill and chance, the largest of which was the daily

skilo game that became a mainstay. Bingo was illegal at the time, but

the law had been rather narrowly drawn, so at the park we played skilo.

Why the law was written so narrowly is not known, but for years a

majority of members of the West Virginia House of Delegates from

Kanawha County had last names beginning with A, B, C, or D, presumably

the result of our former practice of listing candidates alphabetically

on ballots.

Regardless of the reasoning

behind the bingo law, one person who benefited was Natie Brown who

owned the skilo concession. I met Natie the first summer the park was

open. I had just finished the ninth grade and wouldn't celebrate my

15th birthday until October, so the chances of landing what might have

been considered a good summer job were minimal. Like other kids my age,

I started hanging around the park the minute it opened. It was

exciting, and before long I had the opportunity of going to work for

one of the vendors, "Honest John" Swisher, his nickname for himself. I

hired in at $2.00 per day. The park jobs didn't pay much, but at least

they gave a lot of us a chance to learn some responsibility. My sister

Nancy worked in one of the ticket booths for a while that first year

before getting a job at a lunch counter in one of Charleston's five and

dimes.

John owned and ran a grab

bag concession, located in the middle of the midway in front of the

main snack bar, and everyone won something. "Hey folks, come on over.

Fool ol' Charley and win a doo-la-ly." First it's John's voice I hear,

then mine. It didn't matter that neither of us were Charley, the line

usually worked whether I was working the grab bag booth for John, the

duck pond for the Millers or any of the other concessions.

When Swisher wasn't at the

park he was most likely working a carnival or fair someplace, and if

nothing else was happening he could often be found selling men's

hosiery down at Dead Man's Curve. That was down by Dickenson Field

where a near 90-degree right turn connected the four-lane with the two.

There was nothing fancy about the hosiery operation, just the socks and

the large cartons they came in. He'd park the truck and set the boxes

out. A couple of crudely marked signs, and he was in business selling

the seconds, thirds, and irregulars he frequently brought up from the

mills in North Carolina.

If things got slow, he might

even grab a stick and poke around inside a large empty carton as if

there were something in it. Those who stopped to investigate would

often end up buying something. It was hard not to buy from Honest John.

I can't remember his wife's name, but she was a real nice lady who

helped him a lot, either at the park or on the road with him, and

although I was quite young, having me there seemed to give them a lot

more flexibility.

I worked six days a week in

that crowded little grab bag booth, so full of the cheap aluminum

jewelry and other items bought from Mackie Supply, Natie Brown's

wholesale supply company in Charleston. Mackie was located on Virginia

Street across from City Hall where the United Bank Building now stands.

A native of Philadelphia, Brown moved to Charleston about the same time

the park opened and was involved from the beginning. He had been a

highly rated heavyweight boxer in the thirties and had the distinction

of fighting many top contenders, including Max Baer, Maxie Rosenbloom

and Joe Louis. He met Louis twice, losing by decision in ten rounds in

1935 and being knocked out in four in 1937, the second fight being

Louis' last before winning the championship from James Braddock who had

won it two years earlier from Baer.

In Joe Louis: My Life, an

autobiography written with Edna and Art Rust, Jr., Louis had this to

say about their first meeting, "I wanted to make a good impression, but

I was nervous and overanxious. That March 28 was some trial for me.

Natie Brown was what you call a spoiler. He was trying to show me up,

and I could hardly get through his guard. I had him down in the first

round, but he stuck it out for the limit. He was clumsy and had an

awkward style that would make anyone look bad. I decisioned him in ten

rounds, but I didn't feel happy about it." Brown died in 1991 and

Charleston lost a colorful sports figure.

Little is known about the

Carters except that they were related in some way to Cooper, possibly

through Cooper's wife, and they either owned or managed the main snack

bar. One story I remember hearing from either Johnny Denton or Mr.

Carter - I think it was Carter - was that at some time in the past they

had experienced a larger than expected crowd and ran out of hamburger.

Lots of bread he said, but no meat. Instead of panicking they just

crumpled the bread and moistened it enough to form patties, fried it in

hamburger grease and served it bread on bread with garnishments. They

never had a complaint, he added.

On several occasions I

helped the Millers who ran the duck pond. They were a wonderful old

couple who seemed relieved to be living at a slower pace than before.

They once owned several rides and made a lot more money, but as they

got older they seemed content. I liked them and they showed me some

photos from their glory days of old, but by far the most interesting of

all the people I met at Joyland were Bill and Ginger Picozzi. The

Picozzis owned both food and game concessions, and although I didn't

know them well, I must have worked in one or more of their concessions

at some point. I think I worked in every game concession in the park at

one time or another, plus I ran some of the kiddie rides.

I hadn't seen them in over

20 years until about 1980 when I renewed the acquaintance. Bill was

raised in the Little Italy section of Cleveland and, according to Bill,

Jr., a well known Charleston sports and entertainment promoter, "Dad

was a promising boxer who was undefeated after 44 fights when he

decided, toward the end of World War II, to get married." It was his

bride, Virginia "Ginger" Latlip, who had the strong family background

in the entertainment industry dating back to the early 1900s.

Her father, "Cap" Latlip,

had set a world record by plunging 112 feet from a pole into a small

pool, and became a partner in Hall and Latlip Shows which traveled by

rail throughout the eastern states and Canada. They also toured at

times as either The Latlip Family or Latlip Attractions. The family

moved to Charleston around 1917 and have been residents ever since.

They were featured in a 1979 Goldenseal article, "The Famous Latlips,

Charleston's Premiere Show Family" (Volume 5, Number 2).

Until tragedy struck in 1913

in the form of a train wreck, the show was so large it took 37 rail

cars to transport all the equipment and animals, which included horses,

elephants, lions, and tigers. The wreck resulted in the loss of a lot

of valuable equipment and several animals. For a while in the mid to

late thirties until the end of World War II, Ginger and her twin

sisters toured as a trio up and down the Atlantic Coast, and according

to Bill, Jr., "performed with Judy Garland and Bob Hope, and

entertained at USO Clubs during the war." After the war, Ginger married

Bill Picozzi who she had met five years earlier while performing in

Cleveland. They soon put together a full carnival and toured for a

while, before deciding to limit their activities to just a few

concessions and rides

Now their children are

carrying on. Connie has devoted much of her time to dance and beauty

pageant promotions and recently returned to Charleston, and Bill, Jr.

is busy planning his next promotions. When asked what he liked best

about Joyland, Bill replied, "the train ride, I was eight or ten at the

time." When asked what Joyland has meant to him though, his answer is

quite different, "What I took from Joyland and being raised in a

wonderful show business family are those things that have allowed me to

do as well as I have - a lot of common sense, a good nose for business,

and values." Speaking of values, in 1993 the Charleston Gazette carried

an announcement about Bill and Ginger's golden wedding anniversary.

Bill died later that year, Ginger in 1997. I called them after the

anniversary announcement to congratulate them and had a nice

conversation. I'm so glad I did.

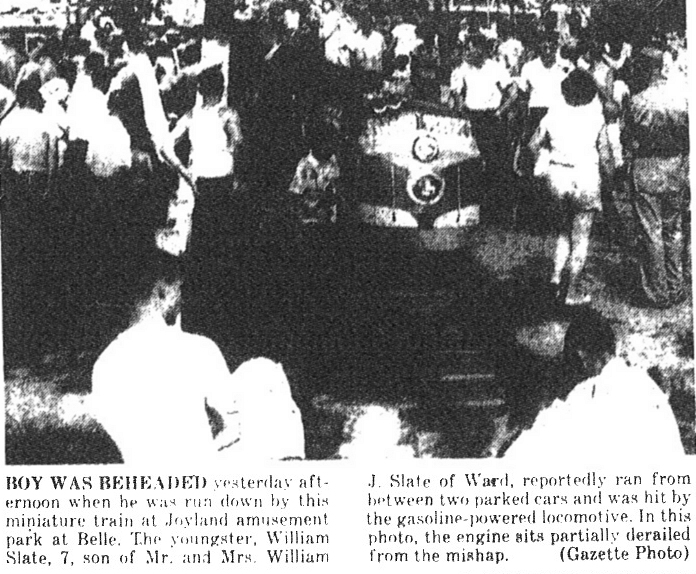

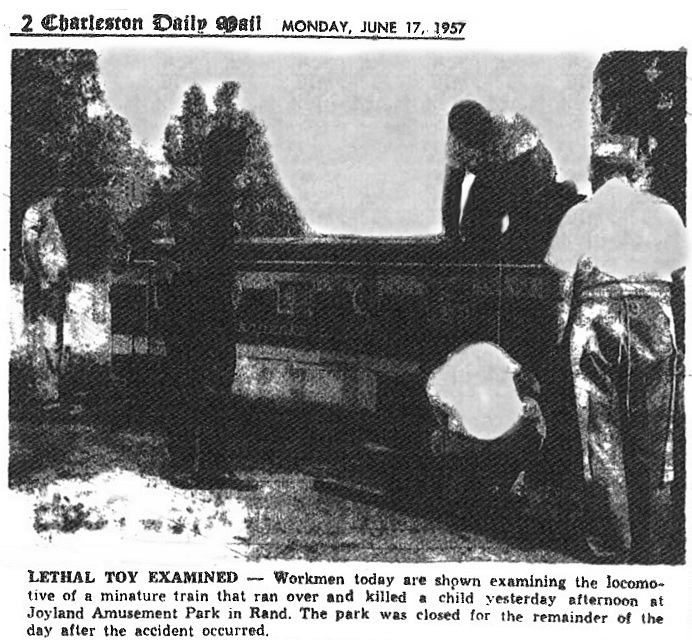

Johnny Denton's decision to

use old equipment at Joyland came at a price, and the park's reputation

eventually suffered. Breakdowns are costly, not only to revenue, but

also to image - and possibly even to safety. Ride operators sometimes

had to double as mechanics, and mechanics as ride operators, and the

distinction between the two at times seemed blurred, giving the park a

"dirty" look. This was not the fault of the workers; it was the hand

they were dealt. Toward the end of Joyland's stay at the grove, a child

was fatally injured when he stepped into the path of an approaching

park train. Coming on top of mounting problems, the accident possibly

hastened the park's closing.

My walk down memory lane has

been a wonderful experience and has made me very appreciative of the

time spent at Joyland. The sounds of the midway got in my blood as a

boy, and I can't visit a park or carnival without wishing for a moment

that I was barking from one of the booths "Hey folks, come on over..."

I learned a lot during those three years, most importantly that these

were good, decent, hard working people that I am proud to say I knew.

Things may not always have been strictly on the up and up, the ducks

with the lucky numbers may not always have been in the water, and the

grab bags with the biggest prizes may not always have been in the box,

but in the bigger picture, the one that really counts, these wonderful

people always brought a lot more smiles than frowns.

|