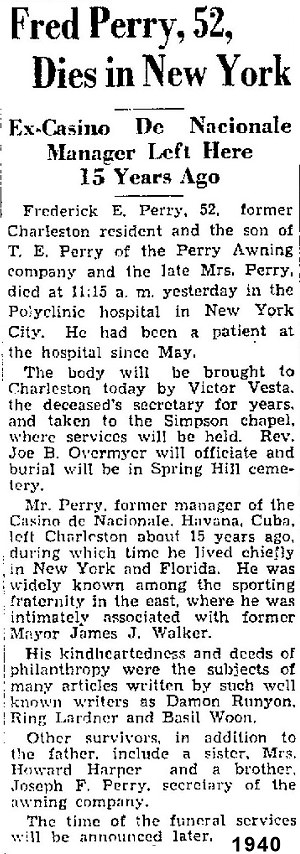

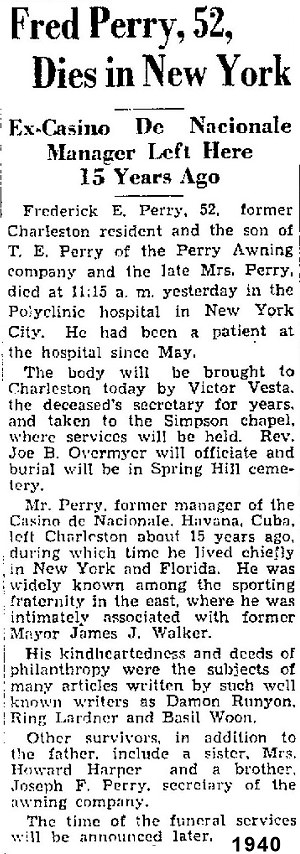

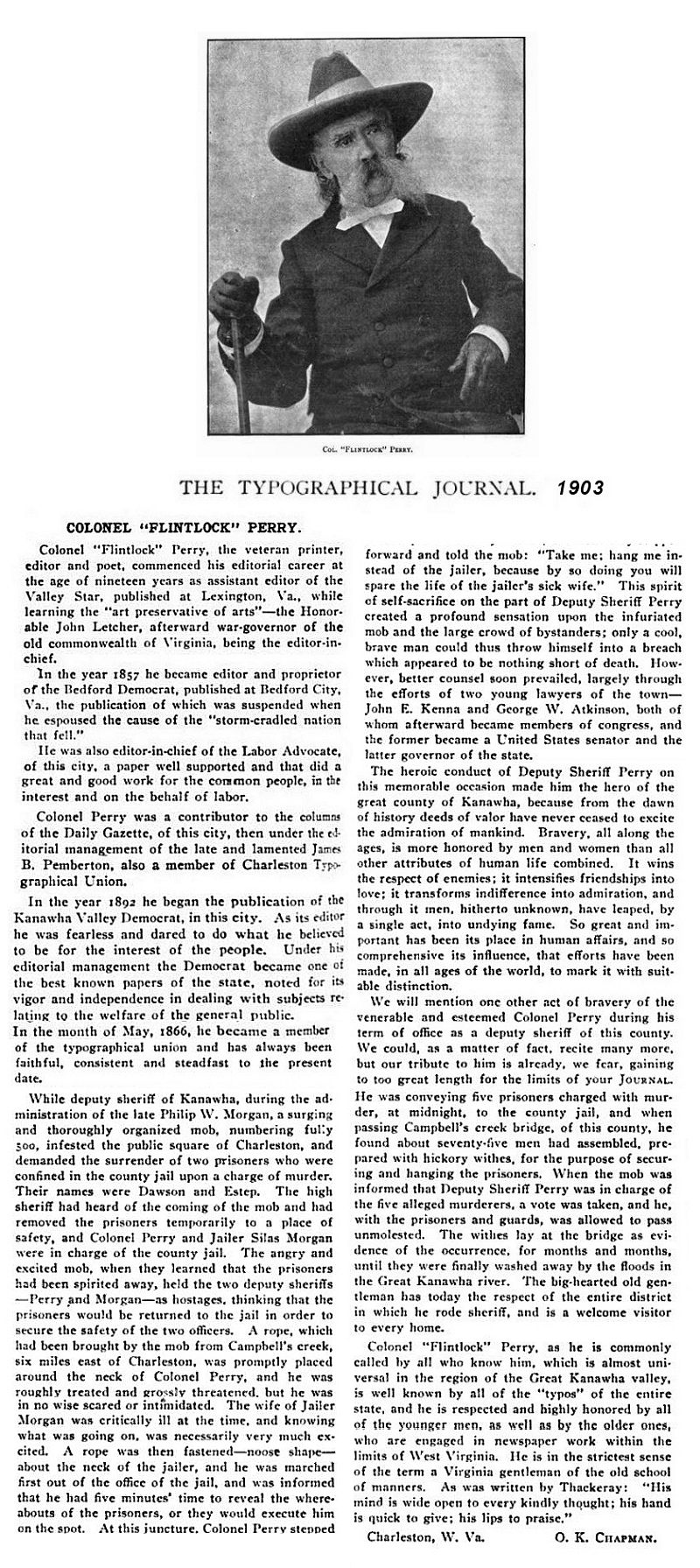

FRED PERRY, THE ELK CITY FLASH

Fred Perry

was born and raised on the West Side of Charleston, known back in the

day as "Elk City". He became the most widely known and popular

gambler of his day. Not counting the money he made in America, he also

made over 7 MILLION dollars in Cuba. But before

we get into Fred Perry's life, let's start at the beginning with his

father:

|

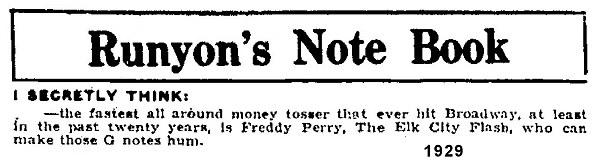

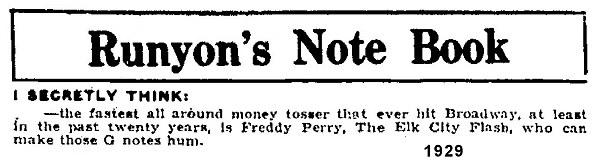

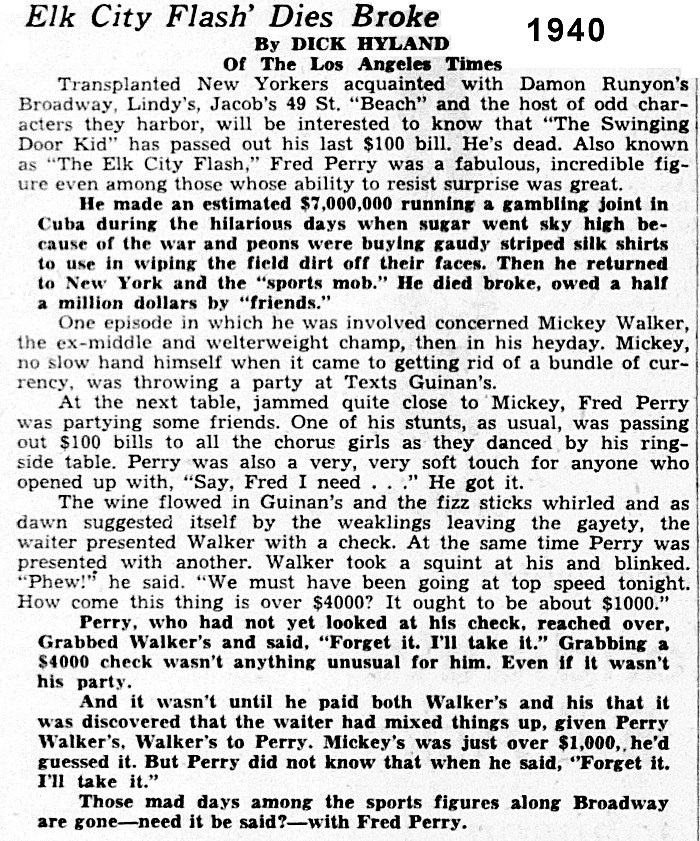

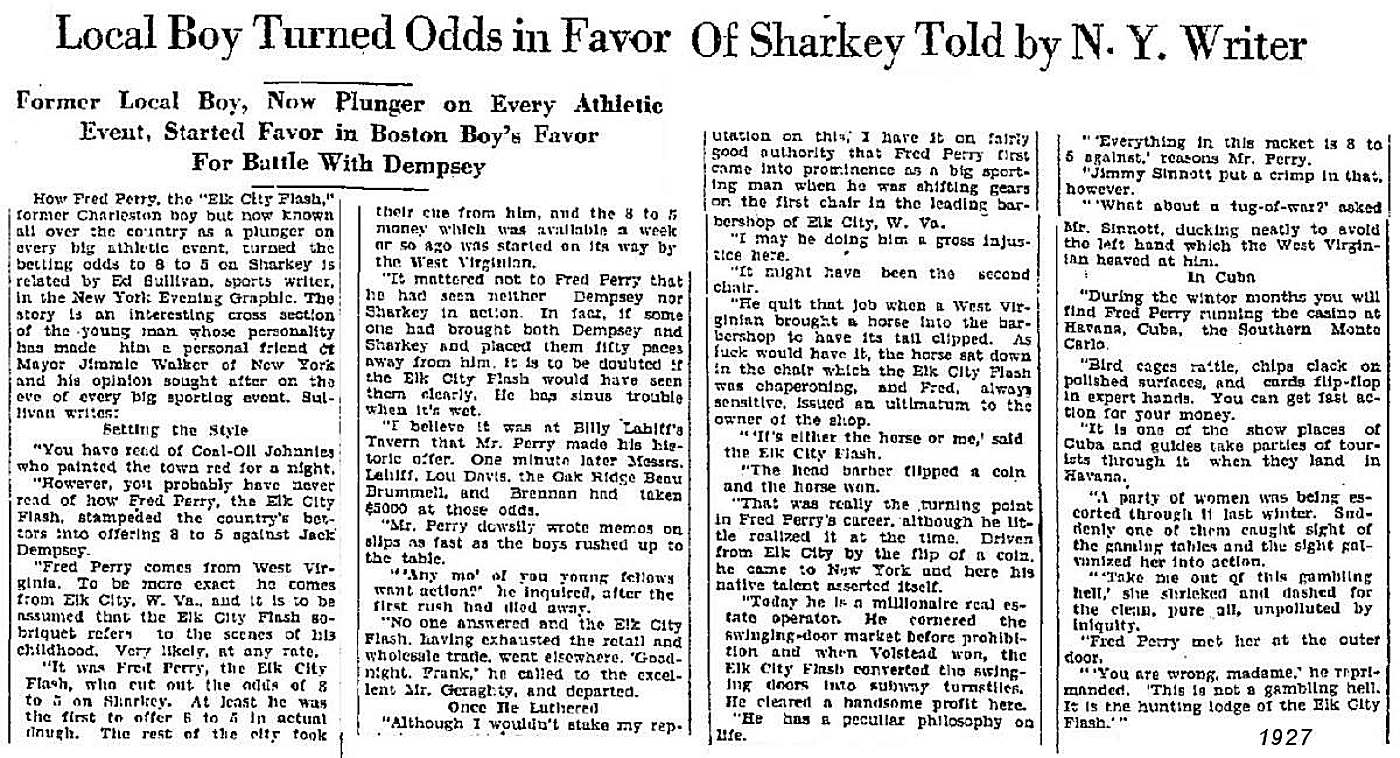

Fred Perry was the most famous gambler in his

day, with stories appearing

all over the U.S. in major

newspapers, like this one from the L.A. Times.

|

Amazing isn't

it? And yet no one remembers the "Elk City Flash". Well, I

am here to correct that and give you the story that nobody today

knows....

Fred Perry was born on the West Side in 1886, and lived at 115 Fayette

St, now Lee Street W. just before he left home in 1905. Below you

will read of his exploits, including his stint at the White Sulphur

Springs Resort....

|

The following is a chapter on Fred

Perry's life from the book

"When it's Cocktail Time

In Cuba"

|

Fred Perry is a "square

gambler."

Charleston, W. Va., 1889. A frame house of some pretension, painted

white. A God-fearing man of gentle features paces anxiously the porch.

Suddenly he halts; sweat breaks out on his forehead; there is a faint —

becoming lusty — cry from within. A woman hurries out and beckons,

speaking softly:

"It's a boy."

1900.... Another house but the same gentle-faced man speaking

to his small son.

"Boy, you are to be raised for the Church, to follow the vocation of

your father. It may be that when you are older you will not feel the

Call. In that case you will go your own way in life, remembering the

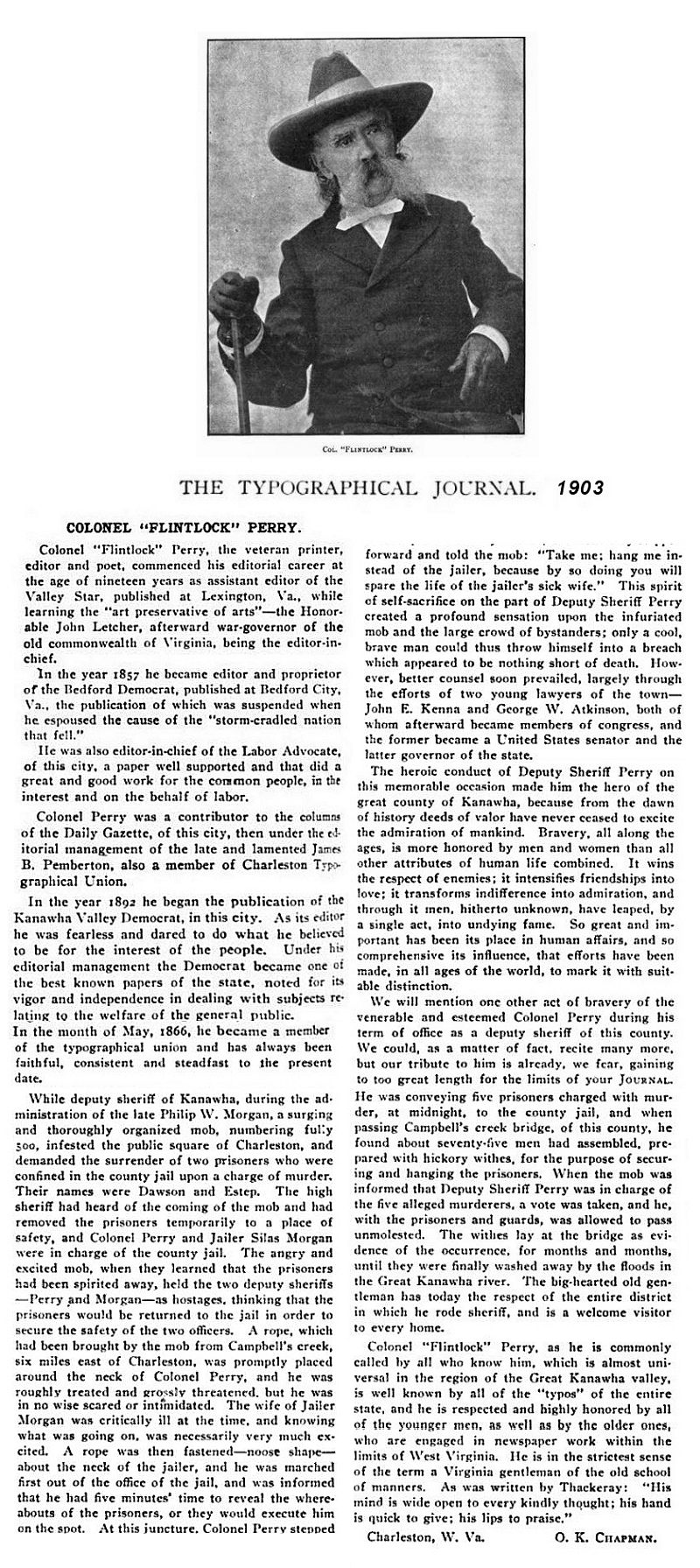

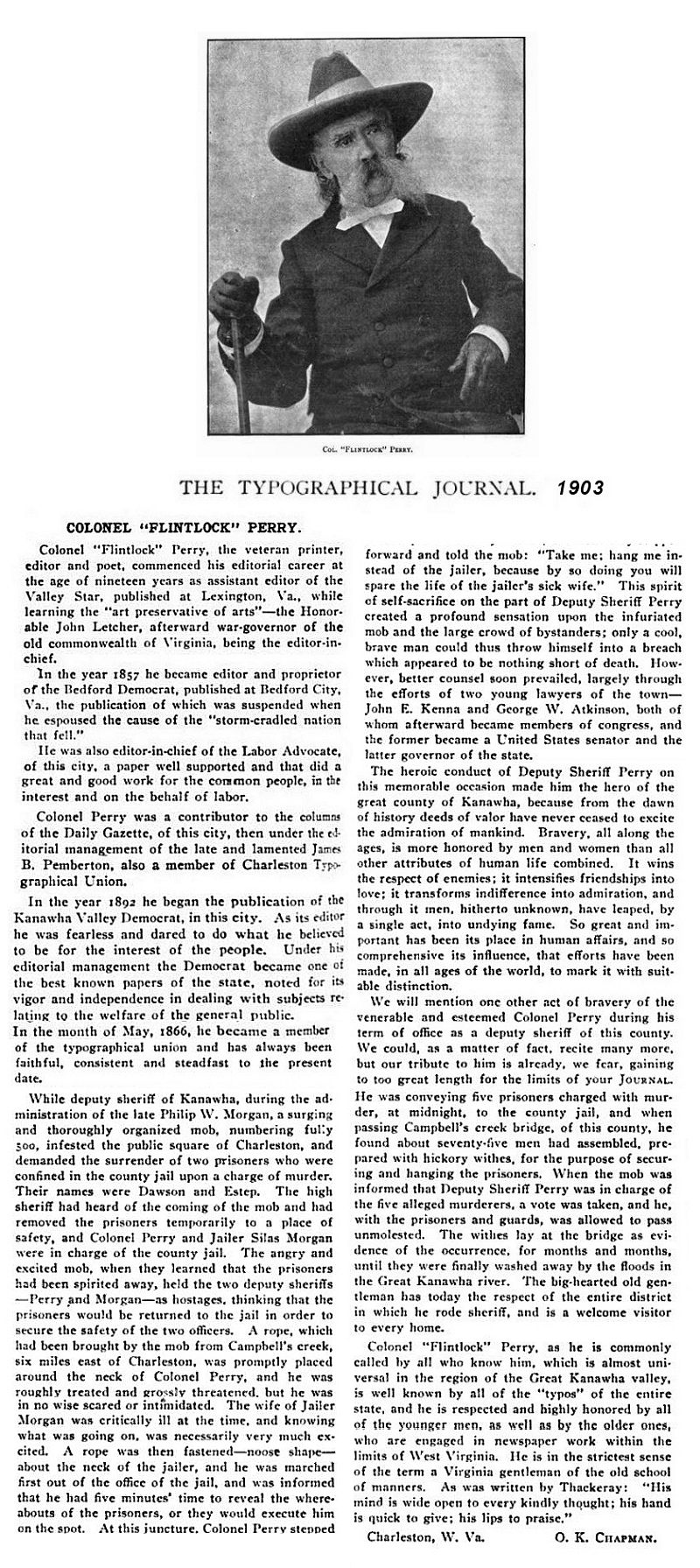

stock you spring from. You'll remember that your grandfather was

Colonel Flintlock Perry, a hero of the war. You'll remember also that

your father was a gentleman, and that you must always be a gentleman,

in whatever paths your life may lead you.

"A gentleman, Fred, means honor, trustworthiness, decency, charity.

Never forget that."

Fred Perry never has. He never "felt the Call" and never entered the

Church, but if he failed in this ambition of his father's the testimony

is overwhelming that he has planned his life according to the other.

"How in the world," I said, "did you ever become a gambler—raised in

that atmosphere?"

Perry was meditative.

"Well," he said, "I guess it just had to be, that's all. I must have

been a throw-back to old Flintlock Perry, who was some lad if all I can

gather is true. Gambling fascinated me the more because it was so

strictly condemned in my home.

"Why, my home was the strictest you can imagine. My mother wouldn't

allow a card or a drop of alcohol to cross the doorstep. One day she

was failing and the doctor prescribed malt beer. She was horrified. She

said she would rather die than touch a drop.

"My father regarded drinking and card-playing in the same light as

murder, adultery, or the other deadly sins. That's why it happened, I

guess. It's an old story. Being forbidden certain things, I set out to

find out why they were forbidden, and found I liked them."

Perry hesitated a moment. Then he said: "I think if father had known

these things himself his attitude towards them would have been

different. Playing cards can't be a sin, because it isn't dishonest in

itself, it's just your skill against someone else's, your luck against

his. All life's that, if you really come down to it. The principles of

life are the same that a fellow goes up against at poker or craps.

"And I've known men in the gambling business who were just as

honorable, to their way of looking at it, as my father was in his own

view. None of the gamblers I played around with for years would take

money from a man if they knew he needed it. Lots of times I've seen

them give it back to a man when they found out he'd a wife and kids at

home."

"Perry," I said, "when did you start to gamble?"

The fair-headed, smooth-cheeked man thought a moment.

"Well," he said, "it wasn't in the Epworth League— ( the Epworth League

is a Methodist young adult association) though there was a kid there

who—but we needn't go into that. I think the first time I ever

saw a gambling game was when I was a page in the State legislature. The

pages used to shoot craps behind the scenes. "I liked to be

thought a 'good sport' in those days, and I got to be a pretty good

crap shooter. Then I started playing pool — and father found out."

"That was the beginning?" I said, gently.

"Yes. There was a row, and I left home when I was nineteen. Went to the

Jamestown Fair with a fellow. Carl—he was my pal—and I were both pretty

fair with a cue and we drifted from place to place making our living in

the pool-rooms. Then we met a civil engineer who offered us a job over

in Joplin, Missouri. That was my first real trip away from home. I'd

never even been inside a theater until then.

"Over in Joplin, which was a pretty wild town, there was an old man

with a white beard named Hanley. He was a professional poker player. He

saw the way I was drifting and tried to get me to go home. But I

wouldn't. I was willful—and scared.

" 'Well, boy, if you will be a gambler you'd better be a good one,' old

man Hanley told me. And he taught me the tricks of the trade.

"Hanley was the one who taught me to respect the viewpoint of the other

man. Always to look behind the words of a man, and not go butting in

with my own half-baked ideas. He said the first thing a gambler had to

be was square, because if he wasn't he'd be shot, sooner or later."

Perry, first with one pal and then with another, drifted around the

Middle West and finally "made a killing" which brought him East again.

He and a gambler named Eddie Young became great friends. Eddie was from

his part of the country.

"A good deal of what I know about human nature I learned from the

gaming tables," said Perry, "and most of what I know about gambling I

learned first from Old Man Hanley and secondly from Eddie Young."

He looked up from where we were sitting in the Casino and, seeing a man

passing, called to him.

"Oh, Eddie!" he said. When the man, short, stockist, with clear,

quizzical eyes, came, he introduced us.

"Sit down, Eddie," he said. "Eddie, I want to see you two meet. . . .

This is Eddie Young of West Virginia, my best pal and my right-hand

man."

Mr. Young and I shook hands.

"Eddie," resumed Perry, "this gentleman wants to write about gambling

and gamblers. Do you think we should let him, Eddie?"

Mr. Young was deliberate. "Wa-al, now," he said, finally, "I don't know

why he shouldn't. Gambling's a business, just like any other. It's a

tolerable clean business, too, nowadays. As clean as any I know of."

"Not only clean, Eddie," said his chief, "but it's the only business in

the world that's got to be clean. If we tried tactics here that some

businesses they claim are 'honest' do we'd be out of business in a

week."

Mr. Young nodded. "That's whatever," he said.

"To get back to the subject," I said, "what happened after you had

become a full-fledged gambler?"

"Oh—I don't know. Just drifted around. Ran a place here and there.

Worked awhile in New York. Got to be quite a boy at golf."

"Golf!" I said.

"Yea, golf!" repeated Perry. "America's greatest gambling game after

poker—and Wall Street, of course."

"He was an amateur champion golfer once," said Mr. Young, with a grin.

"Eddie here thinks it's funny," Perry explained. "Gamblers didn't use

to golf much in those days."

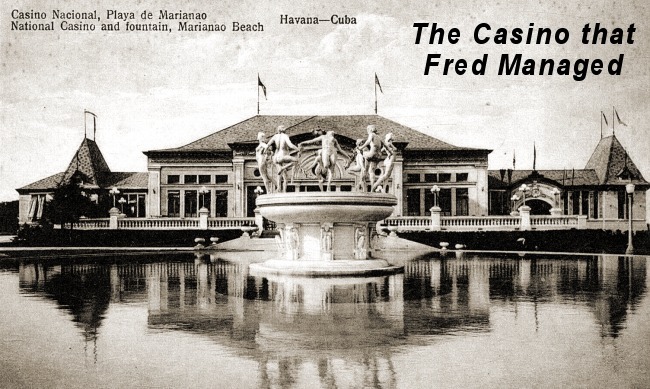

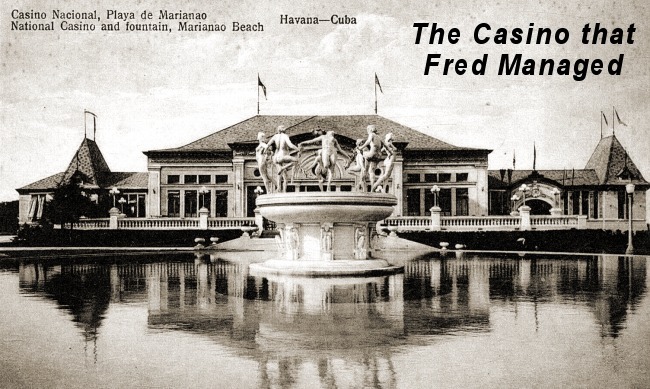

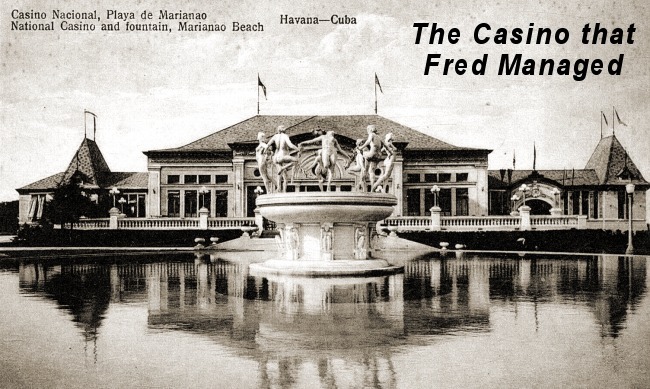

After "driftin' around"

Perry became manager of the club at White Sulphur Springs, West

Virginia.

There he made his

reputation, and it was there that Messrs. Bowman and Flynn found him

and appealed to him to come and

run their casino.

"It's a nice little show," said Perry, "and I've got a fine bunch of

boys working for me—starting with Eddie here." "The boys would go

to hell for him," said Eddie, aside.

I found that this was literally true. Perry has collected dealers and

croupiers from all the reputable houses in the States,* men whose

reputations he knows. Many of them are gray-haired, veterans of the old

open days of California and the Territories. Some worked for Tex

Rickard in the old Concordia Club; others were dealing faro in Tucson

and Phoenix when the Forty-eighth State, puffed up in brand-new

statehood, prohibited public gambling. Men like Holladay, Billy

Stewart, Barton, Barry, Andy Ginter, Cap'n McKeen of Texas, Frank Jones.

"See that little fellow there?" asked Perry, pointing to a small man

whose manner of walking denoted the horseman, and whose frank smile and

courteous ways I had noticed before. "That's one of America's best

amateur polo players, Herbert Wynn. He's not a rich man, though, and

you have to be rich to play polo. So now he's one of my right-hand

men." He called to Mr. Wynn.

"Herbert," he said, "I was just telling this gentleman about you. He's

going to put us in a book. Do you mind?"

* I asked Perry how many "reputable" gambling houses there were. "In

the entire United States," he said, "there are not more than five

places worth a good gambler's time."

"If I was ashamed of my job I wouldn't be working here," said Mr. Wynn,

easily. "This is as good as any other job—as good as selling bonds,

anyway."

"And as hard," put in Mr. Young.

"Is it really hard work?" I asked. I had always heard gamblers referred

to as "soft-fingered idlers."

"So hard," said Perry, "that an hour at a time is a long time for a

dealer to deal without relief. Short of stoking a battleship—and that

shift's two hours— I don't know anything so hard as that."

"A dealer has to be wide awake every minute," explained Young. "It may

look easy, but a good dealer is so fast that it takes a lightning

calculator to keep up with him. And he can't make mistakes. If he does,

the house pays for them many times over. Making mistakes at dealing is

often worse than being downright crooked."

After watching some of the dealers awhile, seeing how deftly they

estimated the number of chips in front of you without counting them,

noting how they made change and paid winning bets without an error, I

was inclined to agree with him.

Young took me to a table and gave me a number of chips.

"Stack 'em up on the hazard table over there and ask Joe how many

you've got," he suggested.

I did so. Joe glanced at the stacks with a casual eye.

"One hundred and sixteen dollars, sir," he said. "Will you take cash?"

Eddie smiled. "Count 'em," he urged. I counted. One hundred and sixteen

dollars!

A man walked into Perry's office in the Casino. He wanted to cash a

check for two thousand dollars.

His name meant nothing to Perry. He offered his card—with a small

middle-western town as address.

"Stranger," said Perry, "if I walked into your place of business at

home and asked you to cash a check for $2,000 when you didn't know me,

would you do it?"

The stranger stammered, cleared his throat, finally thought he would.

"You wouldn't," said Perry. "Here's what I'll do. I'll gamble with you.

Make this check for a thousand and I'll take a chance."

Another man walked into the office, in a towering rage.

"What's this hundred-dollar limit stuff?" he sneered. "Say, this is a

cheap joint!"

Without a word Perry fished out a coin from his vest pocket.

"So you want a gamble, do you?" he said. "Well, in the game you were

playing, there's five percent for the house. I'll tell you what I'll

do. We'll toss this coin and you can call it heads or tails. Or you can

toss one of your own coins. And make it any limit you want. How much is

it? Five—ten—fifty thousand? I'm right here to accommodate—and no

percentage."

The man grinned sheepishly and withdrew.

Sitting with me over supper, Perry watched a woman enter the gaming

rooms. He looked a little disgusted.

"Back again!" he said. "Wait a moment." He called an assistant. "Bill,

that lady is not to play," he said. Then, to me: "We have two of her

checks from last year. She can't afford to play. She only has a small

income and it goes in a night at the tables. We don't want that kind of

money here."

On another occasion, when a certain big gambler from New York objected

to a croupier's rapidity, Perry took him into the private room and

showed him a roulette wheel, a hazard-board and other games. "Name your

limit," he said, "and I'll deal for you myself—and no percentage.

Anything you like up to a million. Or, if you prefer, you can deal, and

I'll play."

A famous humorist lay on his back in a hospital. The appendicitis

operation hadn't quite succeeded. There had been complications.

"Haven't been able to work for three months, Fred," he said. "Tough on

the wife."

An hour later the wife returned and saw a slip of paper on the bed. She

read it, and blanched.

"Fred Perry's been here!" said her husband. "I know," she said. "He

left this. We got to send it back." It was a check for ten thousand

dollars.

I asked a man in business in Havana about Perry. Never have I seen

worship so absolutely flood a man's face.

"Listen," he said, "I'd go to hell for that guy, see? You know when I

started this place I didn't have much capital and what with one thing

and another things didn't look too good. Sugar had crashed and nobody

was spending. "Then the wife took sick, and after that I had to get

sick too. All my savings looked like being swept away. It certainly

seemed my finish.

"Then one night I met this man Perry. 'Hello, George,' he said. He'd

known me in New York— not well, as a friend—only casually. 'Hello,

Fred,' says I. That was all. But he must have seen by my manner that I

was in a hole. Next day he comes to my place and looks me straight in

my face.

"'George, you damn' fool,' he says, 'why didn't you put me wise? How

much do you need?' I tried to protest. 'George,' he continues, 'I could

poke you a swift one, you're so dumb! How much do you need?'

"Well, the long and the short of it is that Fred Perry pulled me out of

a damn' tight hole. You couldn't say 'no' to him. 'Shucks,' he'd say,

'what do you think it's good for, anyway?' That's how he thinks of

money. Something to help out his pals with. And I wasn't even a real

pal."

A night club in New York. A bit of "fluff" is "giving her line" to the

"boy from the sticks," the "free-handed spender."

Fred Perry looked at her with a smile.

"Sister," he said, "you tell me that you've got a dying mother, a

crippled sister, and a brother in jail, not to speak of the younger

brother you're puttin' through school." "It's true, Fred," said the

girl, her voice quavering professionally. "It's true, so help me—"

"Gosh, girl," said the tall man, "I'm not asking you if it's true or

not. You tell it—that's good enough."

The man who told me that story, one of New York's best-known sporting

writers, said that an hour or two later they found the girl all alone

in a corner, weeping over a thousand-dollar bill. "C'n you beat it?"

said the sport-scribe. "She wanted to give it back! Said he was too

decent a guy to bilk."

I taxed Perry with these and other crimes and he merely smiled, his

blue eyes looking into mine humorously.

"Just put me down as a damn' fool and you'll have said it," he said.

It was like the man not to try to deny the tales. A less honest man

would have done so, or pretended to.

When it comes right down to it I don't know of any man whose hand I'd

rather shake, whom I'd rather call friend, than "the Elk City

Flash"—Fred Perry, gambler.

|

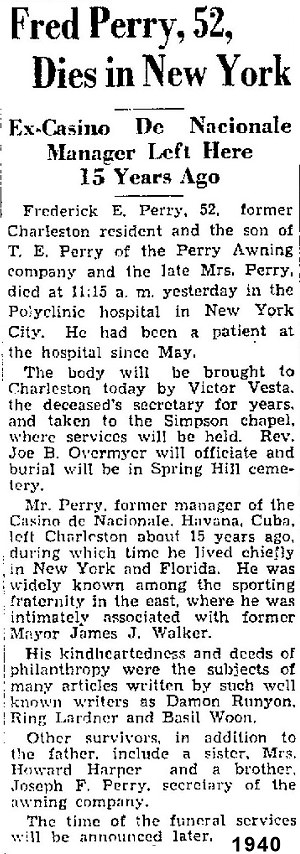

Just a few of

the hundreds of articles on The Elk City Flash

Even Ed Sullivan wrote about Fred Perry

SEE MORE ARTICLES ON FRED PERRY HERE

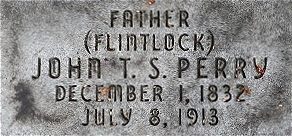

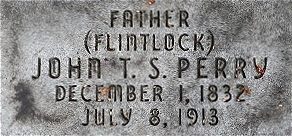

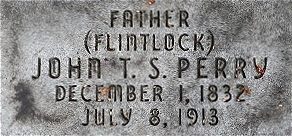

AND NOW ABOUT HIS GRANDFATHER "FLINTLOCK" PERRY

Back

|