Charleston Milling Company "Charmco"

Charleston Milling Company or "Charmco" was one of the oldest businesses in the valley, starting in 1850.

Located

on Morris Street between Baines and Smith, this company made

anything dealing with grains, from flour, biscuit mix, pancakes,

and everything in between including animal feeds. This

building still stands across from the Appalachian Power Baseball

Park. FULL HISTORY BELOW

|

Some of the many products

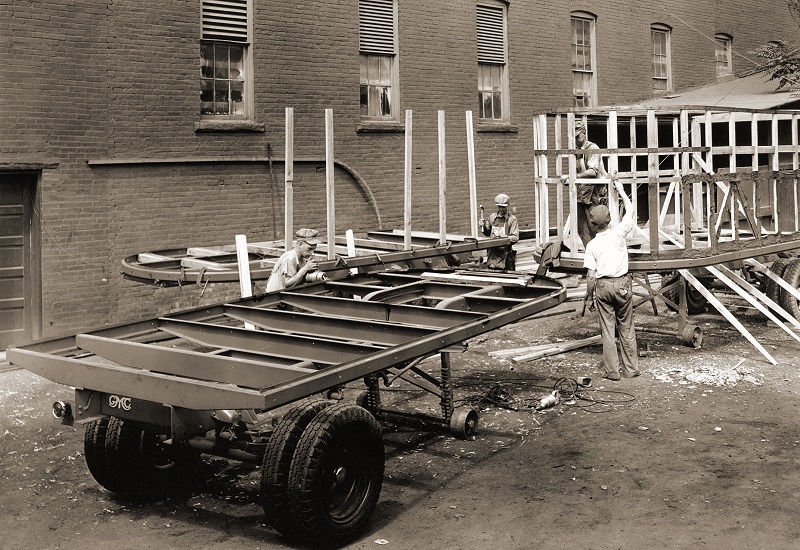

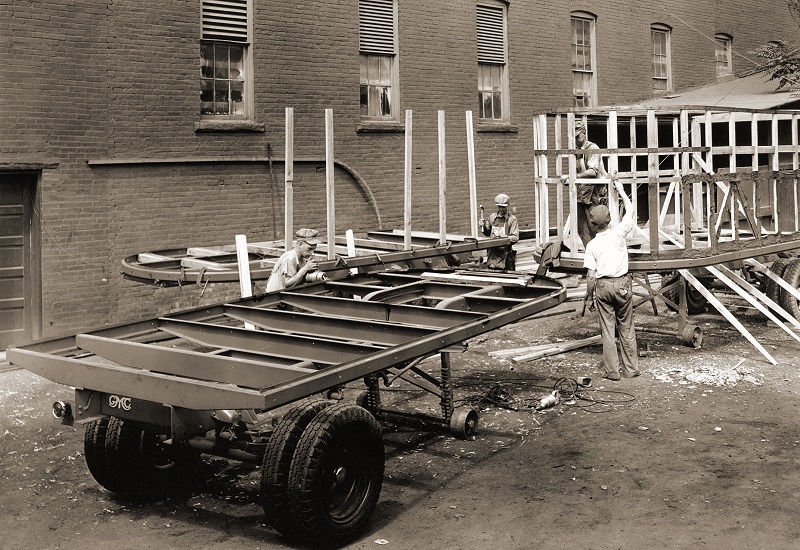

Charmco made all of its own trailers for its tractor-trailers

The mechanics and carpenters showing off a new trailer

Close-up of the gang. One may be your grandfather.

|

This is a private motor home that the gang made from a bus around 1934. The driver and cook unknown.

This had to be one of the earliest and finest motor homes on the road at that time.

In

1952, Charmco's garage burned to the ground with extensive

damage. The fire was caused by a transient who was urinating

behind the garage and tossed a cigarette close to the building.

The garage was not attached to the main building so there was no

damage to the plant itself. This is an excellent shot of Morris Street.

|

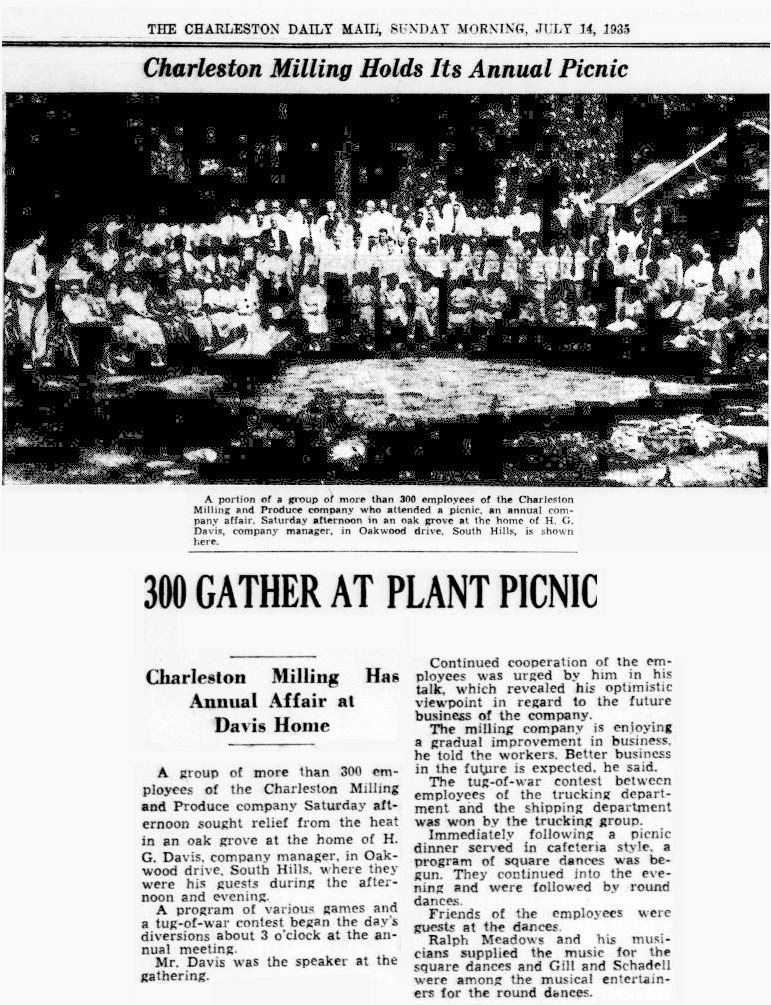

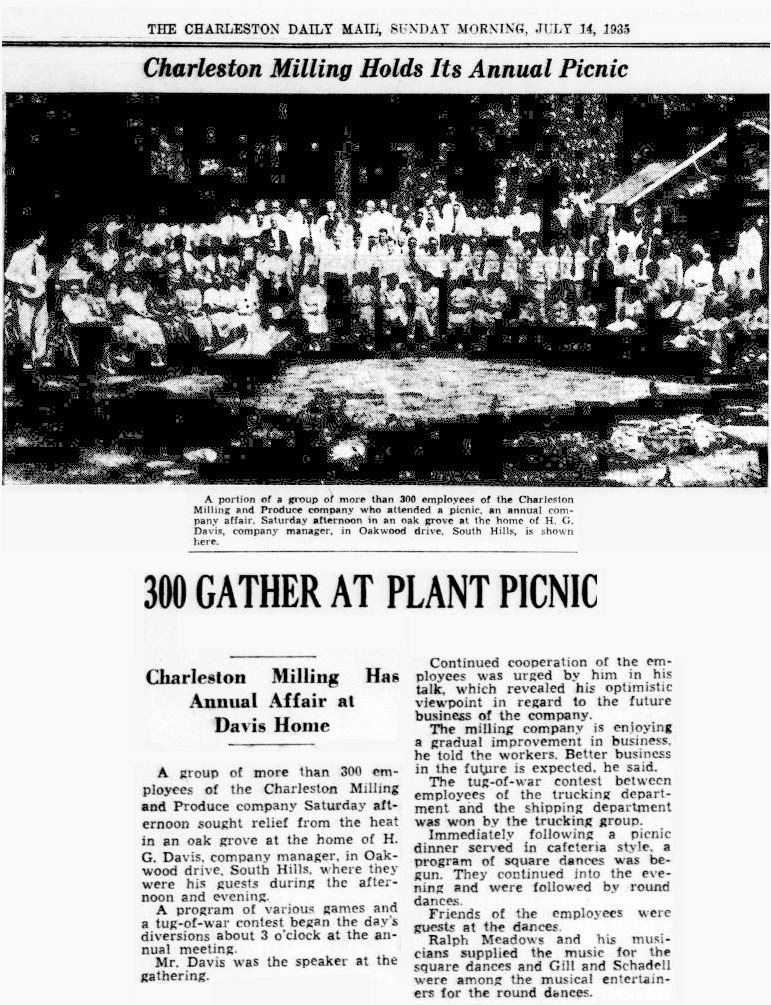

The yearly Christmas party for all the employees.

Included

in the photo is Mr Harvey Davis, President of the company. This

photo was taken at his home at the corner of Oakwood Rd and Corridor G.

The home and beautiful property is still there today. It's

unknown who the others are in the photo, but probably top salesmen and

friends.

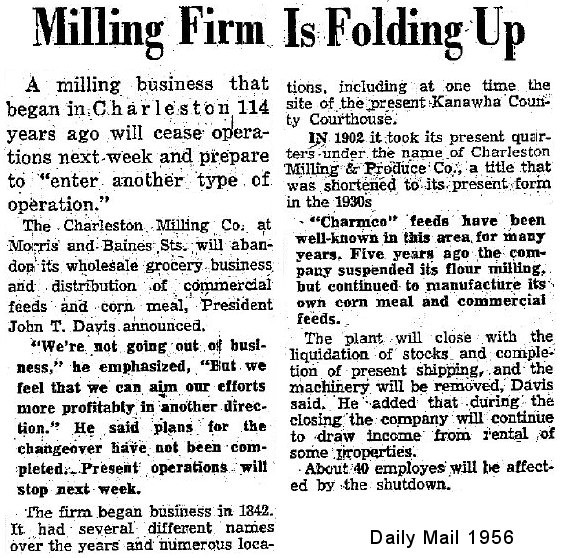

BY 1956, ALL THE BIG BOYS LIKE PILLSBURY, GOLD MEDAL, AND OTHERS BECAME PROMINENT  Kyle Furniture then rented the building for many years as a furniture warehouse. Kyle Furniture then rented the building for many years as a furniture warehouse.

************

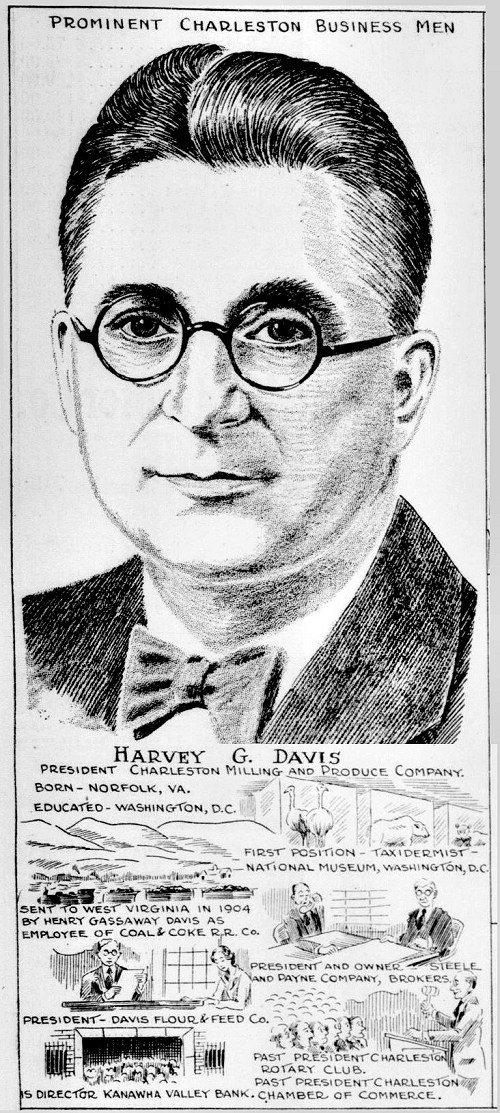

I

find the information below very interesting. Harvey Davis owned

"Davis Flour and Feed" on Kanawha Two Mile before he went over the

Charleston Milling and later to head-up the entire operation. I

would love to know where exactly on Kanawha Two Mile his wholesale

Flour and Feed store was located.

|

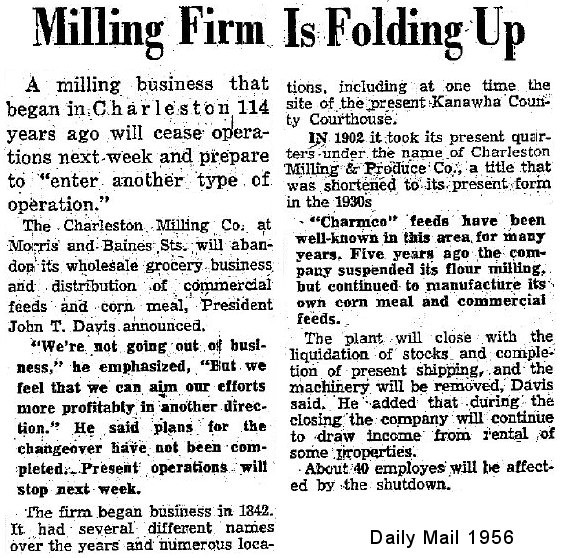

HISTORY OF CHARLESTON MILLING

|

FROM THE CHARLESTON GAZETTE Once

known as “The Charleston Grain and Feed Company,” the mill was moved to

Charleston from Buffalo, in Putnam County, in 1850 to grind

locally-grown grain. The owners first settled the milling company in

Charleston at the corner of Kanawha Boulevard and Clendenin Street.

In

1903, the milling company was reorganized and combined with a wholesale

produce business to form Charleston Milling and Produce Company. It was

moved to a new building at the corner of Morris and Smith streets, and

produced up to 500 barrels of flour daily — until it completely burned

down in 1913.

Within a year, the mill was rebuilt and reopened.

Modern technology (for the time) was included, as were new white and

yellow corn mills. The new mill was capable of producing 800 barrels of

white flour a day, and 600 each of white and yellow corn.

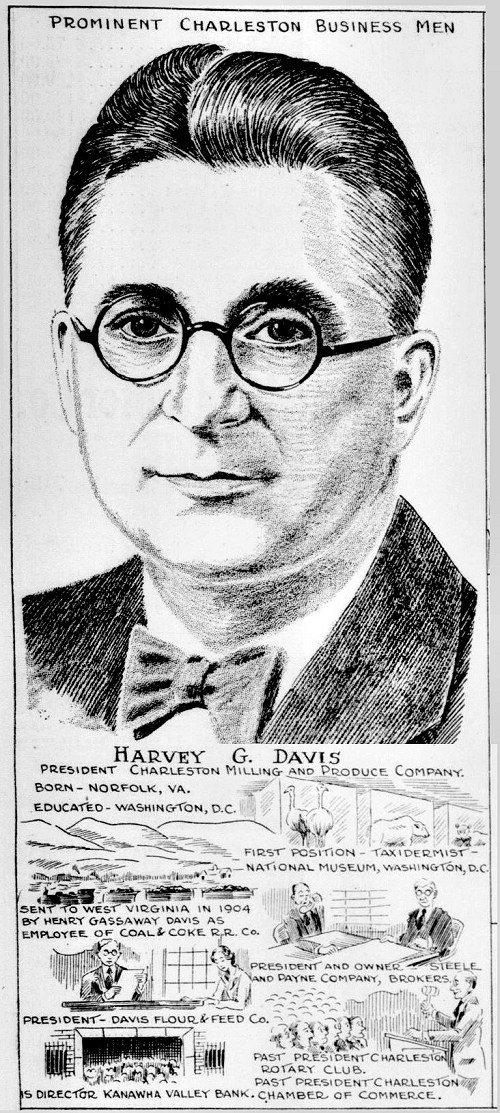

Harvey

Davis, a well-known local entrepreneur who was married to Dorcus

Dickinson, acquired the milling company several years later, in 1922.

At that point, the mill had been in operation for more than 70 years.

Davis,

who had come from Norfolk, Virginia, and had lived in Charleston for

some time, made several upgrades. The company began using motor trucks

for deliveries; before that, all local deliveries were made by

horse-drawn wagon.

The mill’s source of power was changed from steam to electricity, allowing for more flexibility in production.

Also,

until 1923, all commercial feeds sold by the mill were purchased from

large out of state mills. The company soon began producing its own

feeds for cattle, horses, pigs, chickens and other livestock.

The

name “Charmco” came from a contest to name the mill’s new all-purpose

family flour, which was produced from a particular variety of Kansas

wheat. Charmco became the name of all of its products, including its

new pancake flour, buckwheat flour, prepared biscuit flour, self-rising

flour and others.

Over the next four decades, several

improvements were made. Fleets of Charmco trucks were noticed

throughout all of West Virginia.

“Naturally the Charleston

Milling Company has always developed a profitable business, but at the

same time it has been on great service to the community,” reads the

document. “It has been estimated that a company this size, through its

employees, supports around 600 individuals.”

To this day, a small town in Greenbrier County bears the Charmco name, a request granted by the company in 1926.

Once

Harvey Davis died in the 1950s, his son, George, took over the

business. Charmco was transformed into a commercial real estate leasing

company, which George served as the president and chairman of until he

retired more than two decades ago. In 2001, he sold the Charmco

building, built in 1914, to the late Charleston developer Al Summers.

The building still stands, a five-story edifice directly across Morris

Street from Appalachian Power Park, and is available for lease through

The Summers Company.

Though the son of a prominent Charleston

entrepreneur, George Davis always shied away from the spotlight. He

preferred to avoid comments in the media regarding his family’s

business and mostly kept to himself.

When he died from stomach

cancer in May 2017, the last of six siblings, Davis left behind no wife

or children. He had three heirs — two religious entities, which didn’t

want to be identified, and longtime friend Paul Young, who met Davis

when he was 6 years old. Their families attended the same church,

Sacred Heart, and lived near each other in South Hills.

“When I was growing up, he was just like a brother,” Young said.

Among other things, Young said, he was fascinated by the Davis family’s pigeons.

“He

had some that would do back flips and go down so far, and then he had

some that would blow a pouch out in front, they called those pouters,

just different kinds of pigeons,” Young said.

Davis also had

tropical fish and enjoyed riding his Tennessee walking horses. Young

said he lived a very “simple life,” and was very religious.

“He

went to church every day, he went to mass every day and when he got

real bad, he watched it on TV, and sometimes I’d take him communion at

home,” Young said.

Young said Davis studied at a Dominican

seminary, planning to become a priest, before returning home to help

with his family’s business.

He lived in his family’s South Hills

home until his death. Young took care of him and the house, and still

does the latter to this day.

“I still check the house and cut the grass,” Young said. “I did it before and I’ll just keep doing it.”

Young

took the religious pieces from Davis’ home to Sacred Heart and only

kept the kitchen table, which he sat at often, for himself.

“We

went through and marked a bunch of stuff we wanted to keep,” Young

said. “Then I sat down with Steve [Mullins] and Steve said something

like, ‘Do you want to round the corner every time in your house and be

reminded and feel sad that he’s gone?’ and the tags came off.”

Soon,

the historic estate will go to auction, and several of the Davis

family’s antique pieces, including relics from Charmco, will be sold to

the highest bidders.

|

|