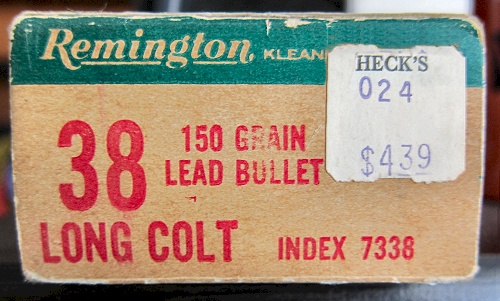

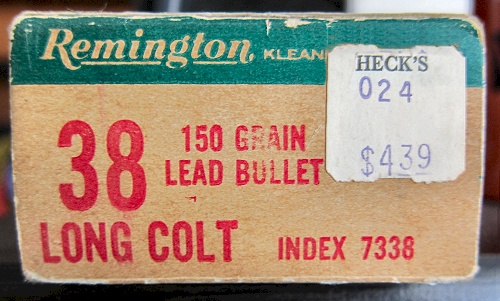

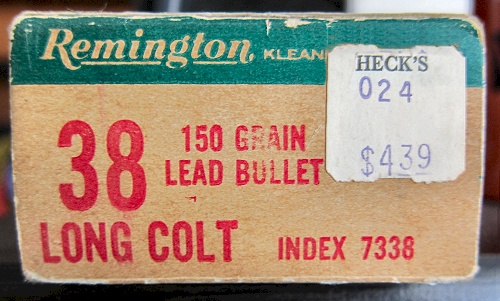

HECK'S

| Heck's

Department Store, a chain of West Virginia based discount department

stores, was founded by Boone County natives and businessmen Fred

Haddad, Tom Ellis, and Lester Ellis and wholesale distributor Douglas

Cook. The Heck's name was a combination of the names Haddad, Ellis and

Cook. Haddad served as President, Lester Ellis was Vice-President, and

Tom Ellis was Secretary-Treasurer. The first store at 1114 Wash.St. E. opened in 1959 |

Kanawha City HECK'S

Heck's

stores were discount, stand alone department stores found in small

cities throughout West Virginia, western Maryland, the Ohio Valley, and

parts of Indiana & Kentucky. Its structure and product lines were

similar to its competitors, Fisher's Big Wheel, Hills Department

Stores, G.C. Murphy's Mart and Walmart.

|

At

its peak in the 1980s, Heck's operated 170 stores throughout West

Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Maryland and Virginia.

Forbes Magazine ranked Heck’s third nationally in profitability and

growth in 1980, beating out Kmart.

In 1983, Haddad retired as

Heck's president and sold his stock in the company. The Ellis brothers

had previously sold out in the 1970's.

Sales fell the following year, and the company saw its first losses in 1984. In 1985, layoffs began, as losses continued.

A

number of factors contributed to Heck’s decline. The U.S. economic

downturn of the early 1980s hit W.Va. particularly hard, and the store

faced increased competition from other chains as well.

|

In

1989 the company emerged from Chapter 11 with 55 stores and under a new

name, as Take 10 Discount Club; a membership club costing $10 to join.

In

September 1990 all of the assets of the Retail Division were sold to

Retail Acquisition Corporation, Inc., and became L.A. Joe Department

Stores. Two locations were sold to, and became, Fisher's Big Wheel. One

Location was sold to Gabriel Brothers

A 1991 Philadelphia

Inquirer article lists several factors for the collapse of Heck’s under

the new management, putting the blame on sweeping changes to the stores.

Specifically,

the Inquirer cited customer frustration with constant store redesigns

and products being dropped from inventory. The store also faced major

troubles from costly data errors caused by its new computer accounting

system.

|

If you're over 50, there's a good chance that you still have something in your house from HECK'S.

|

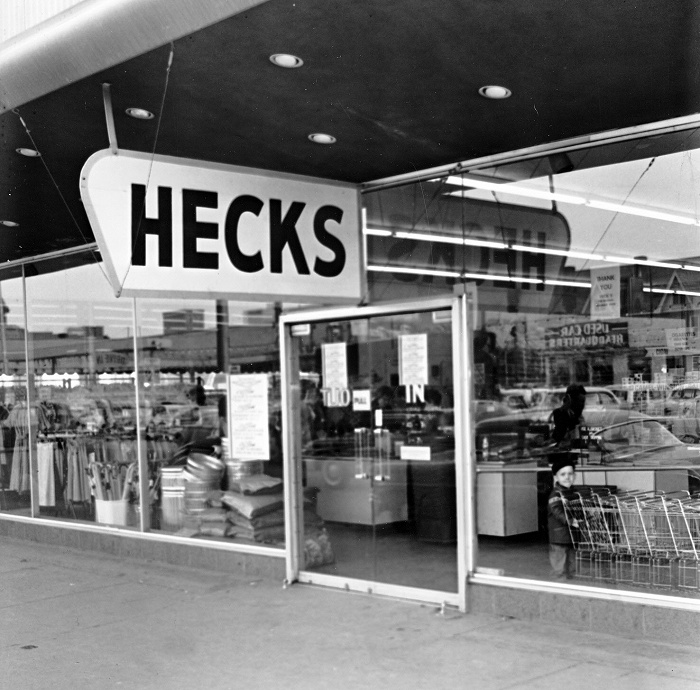

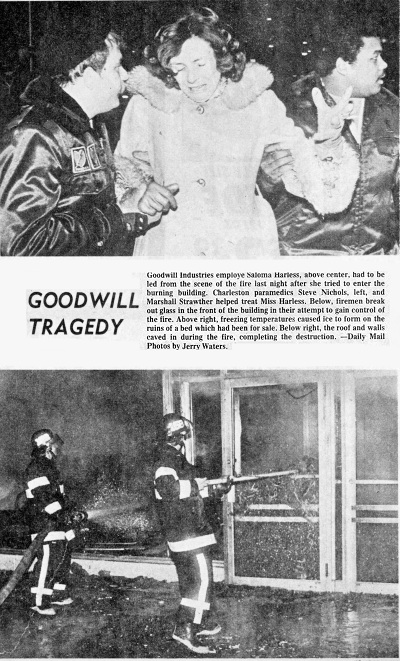

Washington Street East store that would later burn to the ground as a Goodwill store.

Typical interior of an early Hecks store.

In

1977, the Washington Street East Heck's was a Goodwill store.

On Jan 18, in sub zero temperatures, Charleston fighters had a

real situation on their hands. I was off duty and took these

photos.

|

SIDE NOTE:

Ran across this article from 1975 concerning the condition of Capitol Street as a viable business location.

|

On

Aug. 9, 1971, hundreds of shoppers stood in line at Plaza East

(across the street from the current ballpark) , waiting for the 10 a.m.

opening of the new Heck’s store. Owner Fred Haddad said at that time

that it was the biggest opening day in the history of Heck’s. By

closing time, more than 26,000 shoppers had visited the store. The

store replaced an earlier store on Washington Street that years later

burned down. Heck’s was the largest retailing and wholesaling operation

in West Virginia under in-state ownership. Heck’s officials boasted

$500 million in annual sales, $300 million in assets and 8,000

employees. However, by 1987, Heck’s was in bankruptcy. It was purchased

by Jordache, the designer jeans maker, in 1990, which converted the

remaining locations to LA Joe department stores.

|

This

is one of the rarest photos that you will ever see. It's Rayhall

Motors, the Kaiser Fraizer Dealership that opened in 1950. Only

open for three years because Kaiser Fraizer went out of business in

1953. This attractive and unusual building would become the first

HECK'S in 1959. The building to the right behind the dealership is the old Davis Child Shelter.

|

©

COPYRIGHT

All

content including articles and photos on this website Copyright 2013 by

J. Waters. All images on this website are used with

permission or

outright ownership of J. Waters.

All newspaper articles

are courtesy of the Charleston Gazette or Daily Mail for the express

use of the author. You do NOT have permission to use any image, article

or material without permission from the author. You do NOT have permission to pull

photos from this website and post them to Facebook or any other

website. Any

material used without permission will be subject to creative copyright

laws.

|

Epilogue

How death came to a once-prosperous discount-store chain

October 25, 1991

by Donald L. Barlett & James B. Steele, PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER STAFF WRITERS

In

March 1987, Russell L. Isaacs, the chief executive officer of Heck's

Inc., received a singular honor. He was selected by the Horatio Alger

Association as one of 10 people from across the country to receive its

annual Distinguished American Award.

The 54-year-old Isaacs that

month joined a prestigious roster of previous award-winners who ranged

from Bernard M. Baruch, adviser to seven presidents, to Raymond A.

Kroc, the founder of McDonald's Corp.

Intended to recognize

rags-to-riches success stories, the awards are given, in the

association's words, to show young people that "opportunity still

knocks in America for anyone willing to work. "

The association

and its awards are named for the author of the popular 19th-century

novels - Ragged Dick and Luck and Pluck, among others - that recounted

the tales of young boys who achieved success, fame and wealth through

hard work, perseverance, honesty and luck.

The association

described the 1987 winners in general as "role models who give others a

different kind of inspiration to succeed. "

In Isaacs' case, the

association related his rise from an impoverished West Virginia family

- his father was a coal miner and his mother "suffered an apparent

stroke" during the birth of her seventh child - to become chairman and

chief executive officer of Heck's, a discount department-store chain

based in Nitro, W. Va., near Charleston.

The association said it

was most fortuitous that Heck's directors had selected Isaacs, who once

had been the company's chief financial officer, to run the entire

operation: "Giving Isaacs free rein has proven to be a wise decision. .

. . His previous knowledge of the company gave him an advantage in

implementing changes he thought most beneficial to the company. "

Well, not exactly.

Actually, Russell Isaacs had just overseen three consecutive years of losses adding up to $31 million.

He had directed the closing of three dozen stores scattered across several states.

He

had fired hundreds of employees, including Bobby Jean McLaughlin and

many others who had worked at Heck's for 10 or 15 years or more.

And

he had presided over the company's relentless downhill decline - a

decline that in time would lead to the elimination of thousands of jobs.

In

fact, on March 5, 1987 - the week before Isaacs was inducted into the

Horatio Alger Association at a dinner in Washington - Heck's Inc. filed

for bankruptcy protection.

The irony is not an isolated one.

For

Russell Isaacs, the $300,000-a-year chief executive, is little

different than thousands of other executives and investors who have

assumed control of American corporations - from retailing businesses to

manufacturing plants.

He is a financial officer by training. And

by all accounts a good one. But aside from a grasp of the numbers, his

critics say, he had little understanding of the business he was

running, or what made it work.

Listen to Douglas R. Cook, one of

the founders of Heck's who left when Isaacs took over: "Russell is a

certified public accountant and a good financial man. Unfortunately . .

. there's a difference between a financial man and a hands-on manager. "

Cook,

who with three other men built Heck's from a single department store in

Charleston to a chain of more than 120 stores across the

middle-Atlantic states, added:

"I always tell people, if you

started out to destroy a company, you couldn't have done as good a job

as Russell Isaacs did. . . . He . . . tried to make a lot of changes,

tried to fix a lot of things that weren't broken. "

Isaacs has a different explanation.

When

Kmart and Hills built stores "two or three times the size of ours, you

know it doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out you can't compete

with that size store," he said. "Just picture a 40,000-square-foot

store beside a 120,000-square-foot store. Where's the customer going to

go? He's going to go where the selection is the greatest and prices are

the best. "

While Heck's no longer exists and thousands of employees lost their jobs, there were a few notable financial success stories.

One

was Russell Isaacs'. As was the case with many corporate executives and

investors, Isaacs, his managers and those who followed him received

millions of dollars, collectively, in generous compensation packages,

pensions and severance contracts.

By contrast, Patsy J. Perry of

Teas Valley, W. Va., one of the many longtime Heck's workers dismissed

by Isaacs and his successors during a string of failed reorganization

efforts, received little more than $1,000.

The money represented

her pension for 12 years' work. There was no severance pay for Perry,

56, who lives alone and supports herself. There was no interim

allowance to tide her over until she found another job.

More important for Perry, a diabetic who takes insulin daily, the medical insurance that Heck's provided was terminated.

For two years, Perry said, she could not afford regular medical checkups. Her vision deteriorated because of the diabetes.

Still,

she recalled fondly the early years at Heck's. "We were just like one

big family," she said. "In fact, that's what they called it - Heck's

family. "

To understand how that family was born and prospered,

and then withered and died, it is necessary to turn back the clock to

1959. The place is downtown Charleston, in an empty building that had

housed a Kaiser-Fraser auto dealership.

It was there that Fred

Haddad; brothers Tom and Lester Ellis, and Douglas Cook opened their

first discount department store. Haddad and the Ellises had operated

competing stores in nearby Madison, W. Va. Cook was working for a

wholesale distributor.

The new store - called Heck's after the

letters in the names of the founders and two friends - proved an

instant success. A second was opened in 1960 in St. Albans, W. Va.,

Cook recalled, "and about a week or two later we opened our third store

in Huntington. "

Fred Haddad was Heck's chairman of the board

and president, a hands-on executive who wandered through the stores and

knew his employees by name. Cook was in charge of merchandising and

advertising.

By 1963, they had expanded beyond West Virginia, opening stores in Kentucky, Maryland and Virginia.

From

the very beginning, according to Cook, the company was profitable: ''We

showed a good profit. And it was profitable every year up until, say,

1984. "

By 1983, when Haddad retired and sold his Heck's stock, the company had grown to 122 stores with annual sales of $435 million.

Although

net income trailed off in 1983 to $10 million from a peak of $15

million in 1980, Heck's still had posted 24 consecutive years of

profits.

Then it all unraveled.

Haddad was replaced by

Russell Isaacs, who had worked for Heck's in the 1960s and '70s before

becoming executive vice president of Wheat First Securities Inc., a

Richmond, Va., brokerage firm.

Isaacs recruited new managers, introduced new marketing concepts, redesigned store layouts, and added a new computer system.

As

part of the sweeping overhaul, Isaacs said in a report to shareholders,

''each store was planogrammed, a photo-optical process that allocates

product space uniformly . . . according to a master plan based upon

sales. "

"Hence, fast-moving products were given greater shelf

space and a better position than slower-moving items. In addition,

low-profit and marginal products were dropped from Heck's product mix,

an important step in improving store productivity . . . "

The

rearranged layouts, Isaacs said, included "one or more racetrack aisles

leading shoppers to prominent departments through the store. The

racetracks were dotted with speed tables featuring fast-moving and

desirable merchandise to attract shoppers. "

Isaacs concluded

that "though the overall effort was massive and frequently caused

dislocation to shoppers, the initial results indicate a positive

response. "

Well, not too positive.

Despite - or perhaps

because of - the racetrack aisles, photo-optical process and upscale

merchandise, Heck's celebrated its silver anniversary in 1984 by

recording its first loss ever: $8 million.

Along the way,

veteran Heck's employees heard a mounting chorus of complaints from

customers who were irked when they were unable to buy products the

chain had stocked for years but no longer carried.

Like Lucite

paint. Perry said it was one of the biggest sellers in the store where

she worked, but the new management "did away with it and went to

another brand. . . . I know the other paint didn't sell. "

Douglas

Cook agreed. "We had a big following in that," he said. "We had regular

customers. . . . We did a terrific amount of Lucite business. . . . The

first thing that Russell Isaacs' new management team does is throw out

Lucite paint. . . . That's a good example of (why) . . . the customers

get upset. "

The ever-changing store layouts also caused

confusion. "Every time you turned around," Perry said, "they were

changing something. All the customers complained because they never

could find anything . . . "

In any event, Russell Isaacs, fresh

from the experiences of his own investment firm and a satellite Wall

Street investment house, plunged ahead - with more changes.

He

next did what so many other executives were - and still are - doing

when confronted with an ailing business: He sought to acquire other

businesses.

In 1985, he bought another retailer, Maloney

Enterprises Inc., which operated 34 discount department stores in

Heck's marketing area. The selling price was right.

That's

because Maloney's had filed for reorganization under the U. S.

Bankruptcy Code in 1982 and was just emerging from court protection.

The acquisition, completed in August 1985, brought the number of Heck's stores to 166.

That

same month, Heck's picked up a quick $9 million from the IRS by

applying its 1984 net operating loss against taxes paid in earlier

years when the company was profitable.

Even so, Heck's was sinking fast.

On

Sept. 4, 1985, the company borrowed $4 million from Algemene Bank

Nederland NV, a Netherlands bank. Two weeks later, it borrowed an

additional $1 million.

Next, it began firing dozens of workers.

On

Friday, Oct. 11, 1985, Heck's management sat down to decide who would

go. It later seemed to some that many employees selected for

termination were those with the most experience - and the most pay and

benefits.

There was Bobby Jean McLaughlin, now 57, who was

earning $6.20 an hour as a department manager after 18 years with

Heck's. That gave her a base salary of less than $13,000 a year.

And

there was Patsy Perry, who was earning $5.60 an hour as a supervisor

after 12 years with Heck's. That gave her a base salary of less than

$12,000 a year.

During an interview, Perry recounted her

dismissal: "They just came in one morning, the store manager and the

supervisor, and called me and another lady and told us as of today we

were being laid off.

"I was so upset. I asked them if we could

work in a different part of the store if they were doing away with our

jobs. And they said no, they weren't doing it that way. . . . They were

just letting us go. . . .

"They had us to go home as soon as they told us. They thought it would be better if we leave the store immediately, they said. "

Employees were stunned.

"It

was a shock," Perry said. "My mother was here visiting. . . . When I

came home, I cried and cried. She nearly thought I was going to have a

stroke. That night, the girls (from the store) kept coming over to the

house. It was like a funeral. "

The timing of her firing had a

bitter twist for Perry, who had lived for years in her own home in St.

Albans, W. Va., about 15 miles from the store.

"I sold it in

September," she said, "and bought me a little trailer and a lot . . .

so I'd be close to work and I could be here till I retired . . . about

five minutes away. And then I got laid off the next month. "

Other

former Heck's employees, particularly those over 40, found themselves

unable to obtain a job that paid comparable wages or benefits.

Betty

Jean Thompson, a widow, was terminated as a $6.09-an-hour department

manager after 11 years. Thompson, now 60, eventually was hired by

another retailer - but for only 20 hours' work a week. Her new salary:

$3.50 an hour. That represented a 43 percent pay cut. There was no

health insurance. No life insurance. No pension.

For a brief

time, the firings of people such as Betty Jean Thompson and Bobby Jean

McLaughlin and Patsy Perry appeared to stem the tide of red ink at

Heck's.

Indeed, company executives forecast a return to profitability by year's end.

The

optimism was unfounded. As it turned out, Heck's new management team

had failed to detect data errors in yet another of its fresh

merchandising and cost-control innovations - a new computerized

accounting system. The computer, it seemed, abetted by human error, ran

amok.

Price markdowns on merchandise went unrecorded, thereby

creating fictitious profits. Invoices were incorrectly marked, which

led to the reordering of unneeded goods.

A company spokesman was quoted as saying: "When you have computers and people messing up, you have a big problem. "

By the time all the bookkeeping errors had been corrected, Heck's had posted a $5 million loss for 1985.

The

longtime employees had seen it coming. Recalled Bobby Jean McLaughlin:

''I would order six eyebrow pencils. Two or three dozen would come in.

. . . They had people who didn't know what they were doing. "

That

was none too surprising, given the stream of new management recruits.

''That's all you saw," she said, "were people from different places.

They brought people in to show us how to set the shelves and all that

stuff, like we weren't smart enough. They brought all those big shots

in. "

Isaacs labeled the accounting breakdown nothing more than

"a temporary setback in our efforts to return the company to a strong,

profitable operation. "

Nevertheless, to shore up Heck's shaky finances, the board of directors in April 1986 embarked on another money-raising course:

It voted to raid the company's pension fund.

On

Oct. 30, 1986, Heck's informed the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. that

it intended to withdraw $4.6 million of the $7.4 million in the

retirement fund.

Heck's management was going to take 62 percent

of the fund's assets and use them to help bail out the business. That

would leave 38 percent of the assets, or $2.8 million, to be

distributed among 3,251 employees with vested pensions.

That worked out to an average of $861 for each employee.

Isaacs

and Ray O. Darnall, who had served as president and later vice chairman

of the Heck's board, did a little better. According to records filed

with the U. S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Isaacs collected

$134,494 from the terminated pension plan, and Darnall picked up

$397,851.

The pension fund raid failed to shore up the company's shaky finances. Heck's ended 1986 with a loss of $18 million.

On

March 5, 1987, five months after Heck's submitted the pension plan

termination to the PBGC, the company filed for protection in U.S.

Bankruptcy Court.

As the year wore on, however, Isaacs expressed continued confidence in the plan to restore Heck's to profitability.

To

that end, in August 1987 he announced the appointment of a new

president with a similar-sounding name. He was John R. Isaac Jr., who

had worked for several retailers, including Service Merchandise Co. and

a subsidiary of Federated Department Stores.

Russell Isaacs was

enthusiastic about the new president: "We believe his extensive

retailing background will be instrumental in helping Heck's effect the

recovery it has been working so diligently to achieve. I'm just tickled

to death with him. "

John Isaac most recently had been president

of Tradevest Inc., a Florida mail-order company that attorneys general

in several states had labeled a pyramid scheme.

Tradevest

peddled $789 subscriptions to a mail-order purchase club. Once people

joined the club, they could sell subscriptions to others and collect a

commission.

In return for their fee, members were assured they

could earn a rebate of 90 percent of what they spent buying products.

The rebate would come as an annuity - to be paid 20 years after the

purchase.

Soon after John Isaac left the mail-order business to

take over day-to-day operations at Heck's, Tradevest filed for

protection under the U. S. Bankruptcy Code.

But John Isaac was

confident about Heck's. A discount-store trade publication quoted him

at the time as saying that "the company has been making good progress

in redefining its basic core group of stores and in re- evaluating its

future direction. I'm very optimistic . . . "

Once more, the

optimism proved unfounded. Heck's ended 1987 with another loss. In

fact, the loss of $61 million was almost double the cumulative losses

of the preceding three years.

John Isaac, who recruited new

management, including former employees at Tradevest, ended the year by

closing eight more stores and dismissing scores of employees.

By

June 1988, John Isaac had a new plan: He would sell off or close an

additional 40 stores, fire hundreds more employees. A company news

release used all the catch phrases that have become so much a part of

corporate jargon to justify eliminating businesses.

John Isaac

said "the restructuring would enable the company to dispose of assets

which have not provided an adequate return on investment . . . and

which the company believes provide only limited growth potential for

the future. "

It was to no avail. The losses continued to pile up. Heck's stores continued to disappear.

From a high of 166 stores, the retailer shrank to 55 stores. Employment plummeted from more than 7,000 workers to 1,700.

By

January 1990, the name Heck's had vanished; the remaining stores were

renamed the Take 10 Discount Club - as in pay $5 to become a member and

take 10 percent off everything.

Total Heck's losses for 1988 and 1989: $85.5 million.

In

February 1990, the management of Take 10 Discount Club sold the

business to a subsidiary of Jordache Enterprises Inc. The sale price:

$1 and the assumption of $22 million in debt. The remaining stores

scattered across the hills of Appalachia were relabeled L.A. Joe

Department Stores. One year later, L.A. Joe was in Bankruptcy Court.

The stores have since been closed.

One statistical footnote to the collapse of a once-successful regional retailer:

John

Isaac, who earned $360,000 a year in the top job at Heck's, and four

associates who managed the final dismantling of the company, collected

more than $1.5 million in severance pay.

Patsy Perry did not fare so well.

Although

she subsequently found work in a convenience store, Perry said that she

did not make as much as she did at Heck's. What's more, two years went

by before she qualified for medical insurance. During that time, her

eyesight deteriorated and she had laser surgery on both eyes. She also

underwent a hysterectomy.

As for the medical bills run up during the time she had no health insurance, Perry said:

"I still owe almost $4,000 to them people which I can't begin to pay. So I don't know what's going to happen. "

When

she was off work for an extended period, she lost her job at the

convenience store. She since has found another job working about 30

hours a week for minimum wage, and she has some insurance.

The job is at a Value City discount store housed in an old Heck's building.

|

Back to Index

|